Attack on Sydney Harbour: In 1942, Japanese submarines brought WWII to Mosman’s doorstep.

Mosman Bay, 1940s. Image: Max Dupain.

Nobody ever expected Mosman to become the front line of World War Two.

But on a crisp Autumn evening in 1942, as the sun dipped west behind the Sydney Harbour Bridge, the final stage of an audacious plan to invade Australia’s largest city was almost complete.

31 May, 1942. The night World War Two came to Mosman’s doorstep.

Just a few nautical miles off the Heads, six baby-faced Japanese submariners were making final arrangements for their deaths, penning letters and slipping locks of hair into envelopes for loved ones back home.

After a short prayer, the men stood to attention, shattering the moment’s reverence with two sharp claps before downing sake shots.

It was 5:30 pm on Sunday, 31 May.

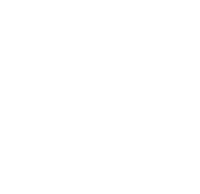

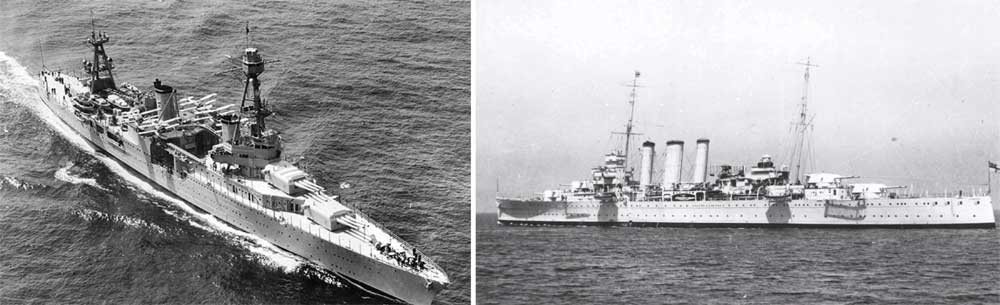

The Japanese Type A Kō hyōteki class submarines that attached Sydney in May 1942 were the same as those used in the attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii in December 1941.

Within hours, they would unleash terror on Sydney Harbour in a night of chaos and confusion that brought war to the sleepy streets of the lower north shore.

Members of Japan’s Special Attack Forces, the young sailors remained calm as they said their last goodbyes and climbed into three midget submarines – each carrying two men and two torpedoes.

Nobody on Terra Firma knew it yet, but the Battle for Sydney Harbour had just begun.

The cruisers USS Chicago and HMAS Canberra were two of the Japanese intended targets.jpg

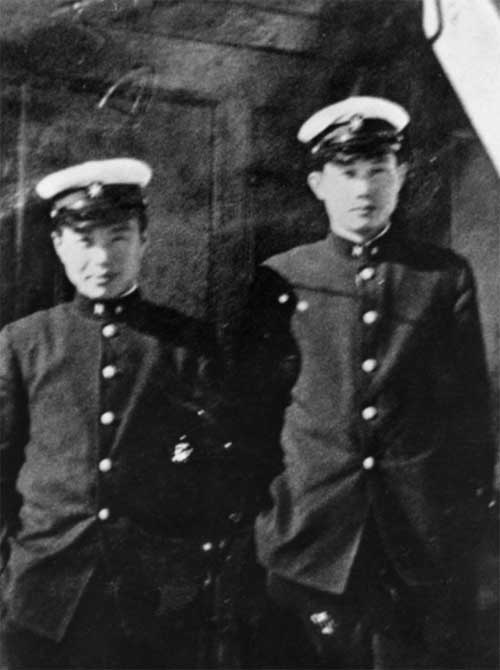

Workers sift through the remains of Kuttabul.

The requisitioned ferry Kuttabul lying on the seabed following M 24’s torpedo attack.

On a daring mission to destroy Allied warships, the state-of-the-art midget subs, M27, M22 and M24 – had their sights firmly set on the American cruiser USS Chicago, anchored at Garden Island after returning from the Battle of the Coral Sea.

The requisitioned Sydney Harbour ferry, Kuttabul, was also docked that night, providing essential accommodation for Navy personnel waiting to transfer to other ships.

At 8 pm, the first enemy sub – M27, manned by Lieutenant Kenshi Chuman and Petty Officer Takeshi Omori, navigated through outer-harbour defences but became caught in anti-submarine nets that had been stretched 1.5km from Georges Head to Watsons Bay.

When the tangled vessel was spotted two hours later, Australian Navy patrol boats went out to investigate. Then, at 10 pm, a converted pleasure cruiser HMAS Lolita dropped three depth charges over the enemy midget.

Each of them failed to explode.

The Japanese crew, now trapped inside the doomed sub, knew their game was up.

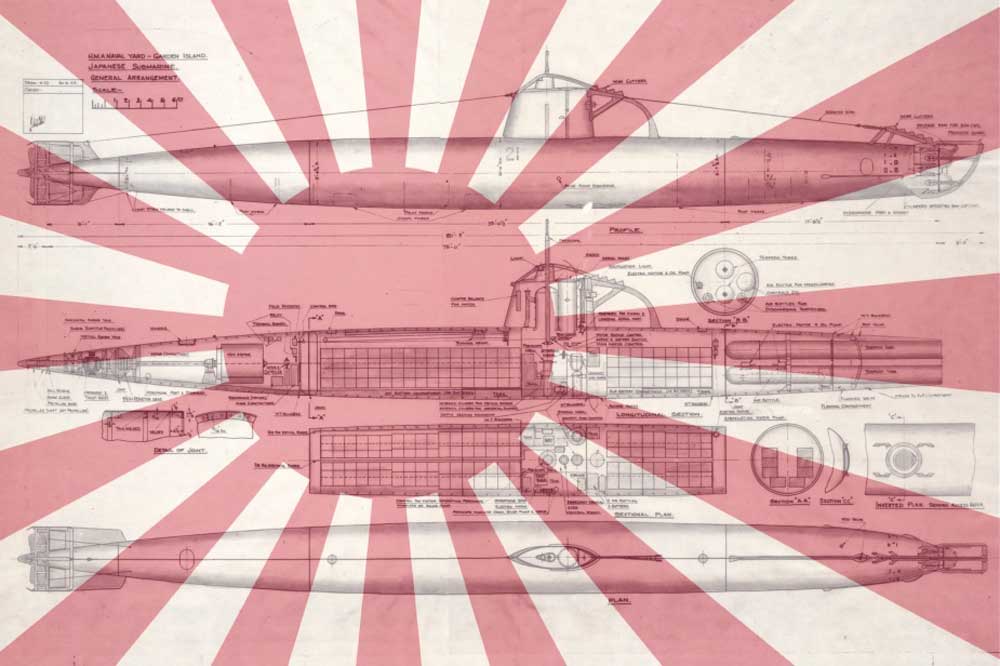

Second Sub LieutenantI Keiu Matsuo.

Second Sub Lieutuant Keiu Matsuo (Right).

It was just seven minutes later, at 10:37 pm when the sailors chose a warrior’s death – destroying themselves and their craft by detonating its 35-kilogram scuttling charge.

The deafening noise of the explosion woke sleeping residents of Mosman before the wailing emergency sirens did, and so began a wild night of panic and terror on Sydney Harbour.

“The harbour was just one mass of light and medley of noise,” Currughbeena Rd resident Philip Dulhunty would later tell reporters, “the thunder of the explosions was terrific.”

Neville Cleary was aged just seven and living in Bond St when he woke to the sound of sirens screaming across Mosman.

“My first memory of the attack was when my mother raced down the hallway in her nightdress – but with her prized fur stole wrapped around her shoulders,” Mr Cleary recalled in a 2009 State Government heritage project.

“She told us that the loud noises we could hear were probably an air attack by the Japanese and that we should take cover.

“Dad, in the meantime, was dragging the dining room table into the hallway, and we all initially sheltered under it.”

The crews of the Japanese midget submarines prior to the attack on Sydney.

As Air Raid Precaution (ARP) Wardens patrolled the streets and terrified families took cover under tables and beds, a second midget, M24, had slipped unnoticed into Sydney at 10 pm, following a Manly ferry bound for Circular Quay.

As fate would have it, 16-year-old Kevin Loughry was heading in the opposite direction on a 10 pm ferry from Circular Quay to Manly when the two boats met at the boom gate, on the Mosman side of the anti-submarine net.

“When the boom gate opened, our ferry from Circular Quay moved through – and then the ferry from Manly slowly started towards the gate,” he said, “the beams from searchlights were scanning both ferries … I got a definite glimpse of what I believed to be a periscope, closely following the ferry from Manly through the gate.”

HMAS Kuttabul after the attack.

It was the M-24.

The submarine was heading west, towards the Harbour Bridge, when all hell broke loose.

At 10:52 pm, the USS Chicago spotted the midget and opened fire.

The Battle for Sydney Harbour was on – and the suburbs of Mosman and Cremorne had front row seats.

David Clegg, a student at Mosman Public School, living in Sirius Avenue, remembers watching the electrifying scene unfold on Sydney Harbour.

Sydney residents inspecting property damage following the Japanese attack on Sydney Harbour. Image: State Library NSW.

“Darwin had (already) been attacked from the air, and we were in no doubt that Australia was vulnerable,” he wrote in a blog post published by Mosman Library, “but to experience an attack so close to home removed any doubt.”

“From the window of our house, we witnessed tracer shells fired from the USS Chicago. At the time, we had no idea what was happening.”

One newspaper report describes “hysterical women” screaming as the ack-ack of machine guns and flashes of light pierced suburban streets that had been plunged into darkness.

“In Mosman and Cremorne, hundreds of people wearing dressing gowns and overcoats streamed into the streets to be escorted to shelters,” it says.

Another describes residents crowding onto verandas to watch the deadly fireworks, with their “glowing cigarettes making pinpricks in the night”.

In his bestselling book “Mosman – A History”, author Gavin Souter describes the incredible battle scene played out, as Allied ships hunted down the M-24.

“The harbour became a son et Lumiere of shells, depth charges, pom poms, searchlights, flares and smoke, which many residents took for a Japanese air raid,” he writes, “Mosman could fairly be said to have been right on the front line.”

At 1:30 am, M-24 re-entered the fray from its hiding position in Bradleys Head.

Sub-Lieutenant Katsuhisa Ban, 24, and Petty Officer Mamoru Ashibe, 25, fired two torpedoes across the harbour, aimed at the USS Chicago, both missing the 182-metre American ship.

HMAS Kuttabul wasn’t so lucky.

One torpedo had run ashore on Garden Island, failing to explode. The other passed under a Dutch submarine, striking the seawall next to HMAS Kuttabul.

Kuttabul was broken in two, killing 19 Australian and two British sailors and wounding ten.

M-24 then left Sydney Harbour.

Sydney Harbour 1942.

To avoid becoming ‘sitting ducks’ from further attacks, HMIS Bombay, HMAS Whyalla, HMAS Canberra, USS Perkins and USS Chicago immediately prepared to leave the harbour. On their way out, USS Chicago spotted a periscope … it was the third submarine, M-21.

At 3.50 am, the converted passenger liner HMAS Kanimbla fired on M21 in Neutral Bay. It was sighted again in Taylors Bay around 5 am, and HMAS Seamist dropped two depth charges.

The cruisers USS Chicago and HMAS Canberra were two of the Japanese intended targets.jpg

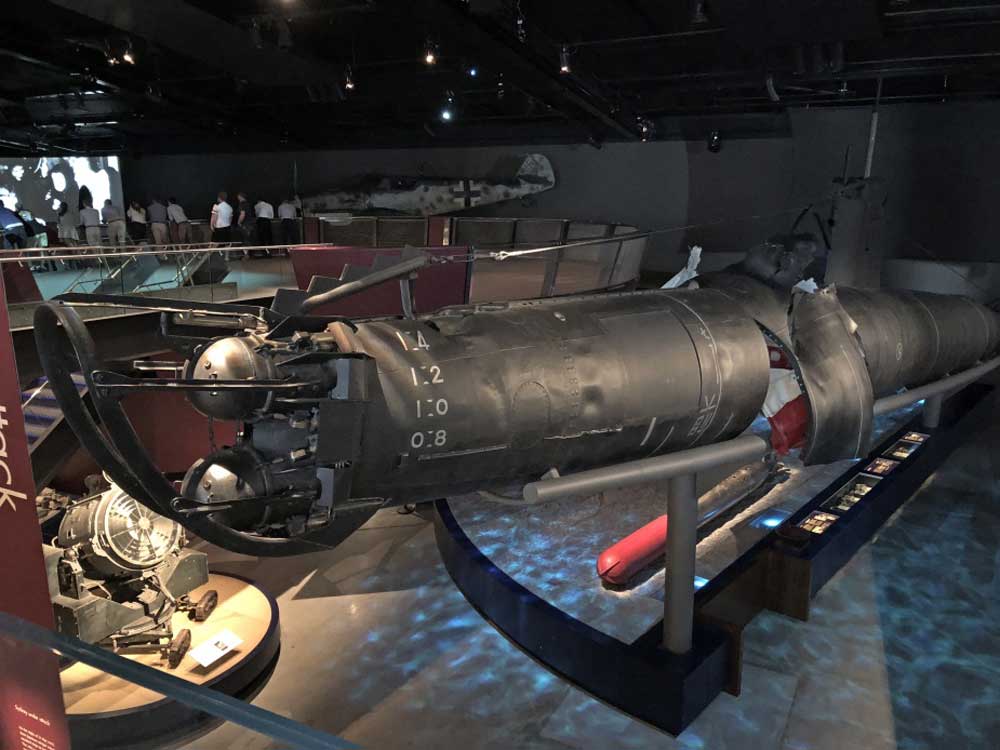

The composite midget submarine now on display in the Australian War Memorial, Canberra.

The submarine surfaced and then sunk. A barrage of 17 depth charges followed from HMAS Steady Hour. Inside the crippled, cramped, hot and airless submarine, the crew of M21, Lieutenant Keiu Matsuo and Petty Officer Masao Tsuzuku shot themselves.

In a move widely criticised by the Australian public, four of the recovered Japanese sailors were given funerals with full military honours.

Two subs were recovered shortly after the attack, where they remain on display at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

Get The Latest News!

Don’t miss our top stories delivered FREE each Friday.