Anzac Day 2019: Acclaimed author Patrick Lindsay on 100 years since the end of World War One.

By PATRICK LINDSAY

Over the last four years, year by year and battle by battle, we’ve commemorated the centenary of World War One.

2019 marks the Centenary of the Great Homecoming – the start of the aftermath of that war – the realisation of the cataclysmic damage that it caused – and

It also marks the centenary of the official end of the war, in June 1919, when the Versailles Peace Treaty was finally signed.

The armistice of November 11th, 1918 that we commemorate each year as Armistice Day or Remembrance Day, was actually just a truce for a ceasefire.

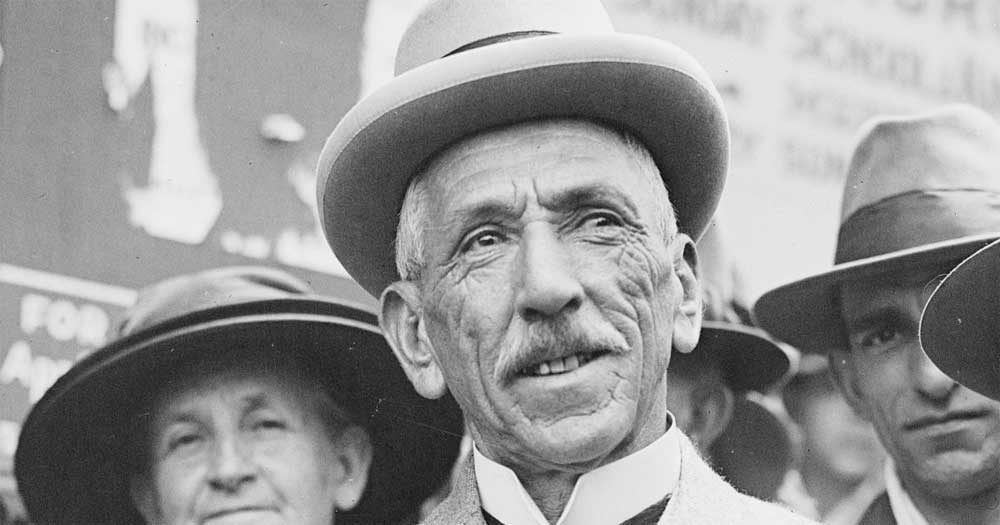

Two days before, our then Prime Minister, Billy Hughes, was to sign that treaty in Versailles.

Journalist, author and local resident Patrick Lindsay.

Prime Minister Billy Hughes.

The delegates were told that they would have to affix their national seals in wax on the document when they signed. Now, that was a problem for Billy Hughes and his team: Australia had no seal of its own.

So Hughes scoured the Paris antique markets, trying to find something suitable, without any luck. Finally, someone had a wonderful idea: they fashioned a seal from the tunic button of a digger’s uniform. And so Australia’s first treaty as an independent nation was signed, with a symbol of the 60,000 diggers who died in the conflict.

Sadly, even before the world began its recovery from the war, it was hit by the global Spanish flu pandemic, which killed 50 million people around the globe – almost three times more than the war!

It was actually the opposite in Australia: our war deaths outnumbered flu deaths by five to one.

Today, one hundred years later, it’s hard for us to imagine the devastating impact the first world war had on countries all around the world. It wiped out the flower of an entire generation.

Spanish Flu epidemic Australia.

Remarkably, clear evidence of that devastation still lingers on those battlefields today. And each year in north-eastern France and Belgium they gather what they call ‘The Iron Harvest’, the annual collection of rusted unexploded ammunition, gas shells and shrapnel ploughed up by local farmers.

Bomb disposal teams collect around 900 tonnes of this deadly harvest every year in France and another 250 tonnes in Belgium.

That’s not surprising when you realise that the battle for Verdun alone lasted 303 days, leaving just under a million dead and a further 1.25 million injured. It worked out at 1000 dead for every square metre of territory fought over.

Today, the central area of that battlefield has been declared as zone rouge or red zone. The definition of zone rouge is: “completely devastated, damage to properties 100%, damage to agriculture 100%, impossible to clean, human life impossible”. Experts claim it will take 500 years before some areas around the Somme are free from that deadly harvest.

Piles of munitions from Somme battlefields.

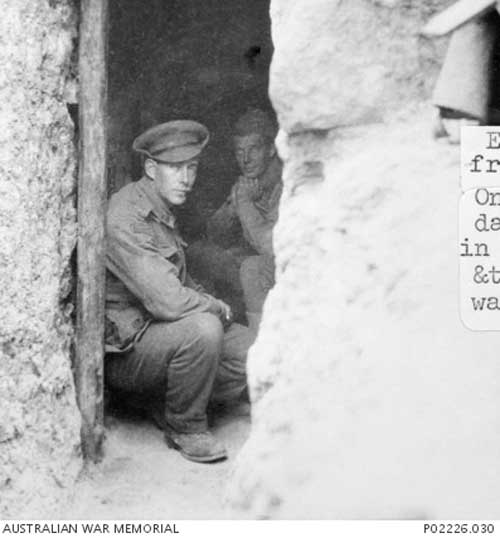

Australian Diggers in France. Source AWM.

Against that backdrop of death and destruction, the ANZACs’ contribution stands out starkly. Our World War One Diggers suffered proportionally more deaths, wounds and illnesses than the armies of Britain, Germany, France, the United States or Canada. And this damage was visited on more than half of the eligible Australian males between the ages of 18 and 55.

One Australian scholar, Dr David Noonan, who forensically researched our records, believes that just three percent of diggers who served in theatres of war in World War One were left unscathed.

One in every four Australian families lost a husband, a son or a brother in that war … imagine how many more lost a cousin, an uncle or a friend? In fact, experts now reckon every second Australian family suffered a loss from that conflict.

The scale of the first world war was simply astonishing … 65 million men took up arms from around 50 nations – and over four years, 37.5 million people were killed, wounded, taken prisoner or went missing.

At the time our population was fewer than five million … so, roughly 2.5 million men. Of these, 416,000 enlisted. One street in the then working-class suburb of Paddington, Bent Street, had 30 houses. It sent 29 men off to war.

To put things in perspective: based on our current population, it would be the equivalent of two million enlisting, with 300,000 killed and almost a million wounded.

Some experts now believe that the 62,000 Diggers who died in the conflict were joined by at least that number again of returned veterans who died in the first decade after the war: those who succumbed to their illnesses or injuries, or, who took their own lives.

And then there were the missing … 23,000 Diggers were listed as missing … those who simply disappeared in the deep fog of war. Imagine their families? … dealing with the nagging doubt of not knowing what had happened to their loved ones?

The story of the missing Diggers from the battle of Fromelles shows how the war even today has a lingering impact on hundreds of Australian families. At Fromelles, a tiny village in north-eastern France, the Diggers fought their first battle after Gallipoli and their first on the Western Front in France, on 19 July 1916.

It was an unmitigated disaster. Of the 7000 diggers who attacked, almost 2000 were killed and 3,500 were wounded or captured – in 12 hours. To this day, it was the worst night in Australia’s history. We lost more men on that day than we did in total in the Boer, Korean and Vietnam wars and all subsequent conflicts.

Of the 2000 who died at Fromelles, almost 1,300 were declared ‘missing’ and their families were thrust into that terrible netherworld, not knowing how their loved ones had died or even whether they had died at all.

Some mothers kept their front veranda lights on for the rest of their lives, in case their sons came home.

Thanks to the work of a Greek-born, retired Melbourne art teacher and amateur historian, Lambis Englezos, we learned that the Germans had buried 250 Diggers who were killed at Fromelles in a mass grave.

Since then, using DNA-matching with descendants, 166 of those 250 Diggers – or two-thirds of them – have now been identified and given graves and headstones in the newly-created Pheasant Wood Military Cemetery in Fromelles.

In fact, another seven missing Fromelles Diggers will be given an official burial and headstones on this year’s anniversary of the battle, as the work of Lambis and his team continues.

Sadly, the impact of the war on many of those who actually survived and returned home was almost as devastating as it was to those they left behind in France. One young man’s story illustrates this perfectly.

Rowland Lording was born in Balmain. He’d just turned 16 when he enlisted on 19 July 1915.

He trained as a signaller and served in Egypt before arriving in France just in time to take part in the battle of Fromelles. Young Rowley was dragging signal wire across no man’s-land when a machine-gun burst caught him and shrapnel penetrated his back, leaving him with massive wounds to his chest and arms and semi-paralysed.

He was given up for dead but, against all the odds, he survived and was dragged back to his lines by his mates. He was bedridden in England until January 1917, then returned to Australia. Rowley Lording endured 53 operations over the next 15 years, with six ribs removed and his right arm later amputated.

Despite living in constant pain, Rowley married, had three children, built an accountancy business, founded the 30th Battalion Association, worked for limbless soldiers and wrote a truly remarkable book about his experiences in 1935.

Sadly, in trying to combat his constant pain, Rowley became addicted to morphia and his life began to unravel. He died in 1944, aged just 45 – another uncounted casualty of ‘the war to end all wars’. For so many veterans, like Rowley Lording, the war never ended.

So how did Australians deal with their grief? The reality was that few families would ever be able to visit the grave of their loved ones on the other side of the world. Travel in those days was a genuine luxury.

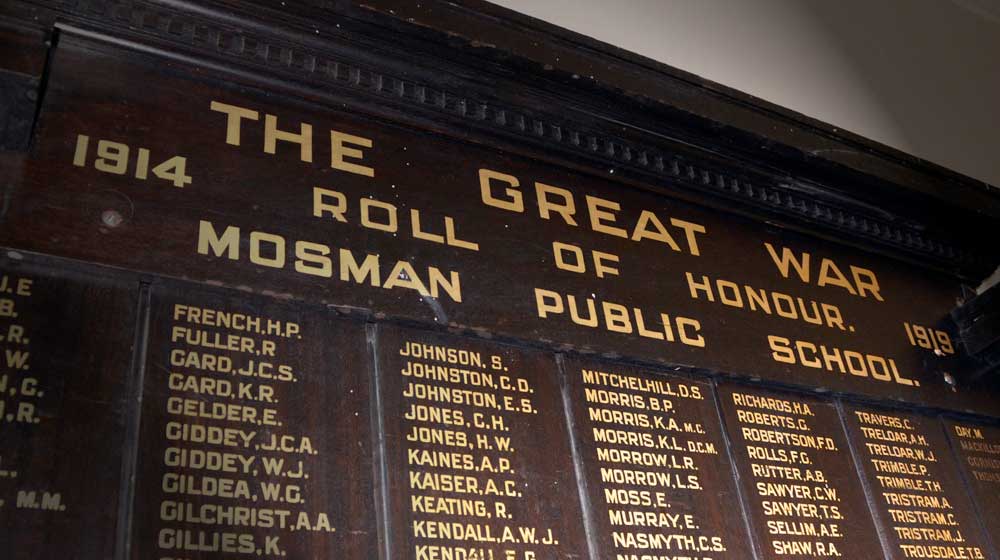

So, we built memorials. Cenotaphs and memorials sprung up in every town and suburb across the nation, immortalising the names of the fallen and giving grieving families a sacred place where they could honour their loved ones and where they could project their emotions and memories in their own ways.

So why is it important for us to reflect on a war that ended more than 100 years ago? Because “to understand where we are going we must understand where we’ve come from.”

Get The Latest News!

Don’t miss our top stories delivered FREE each Friday.