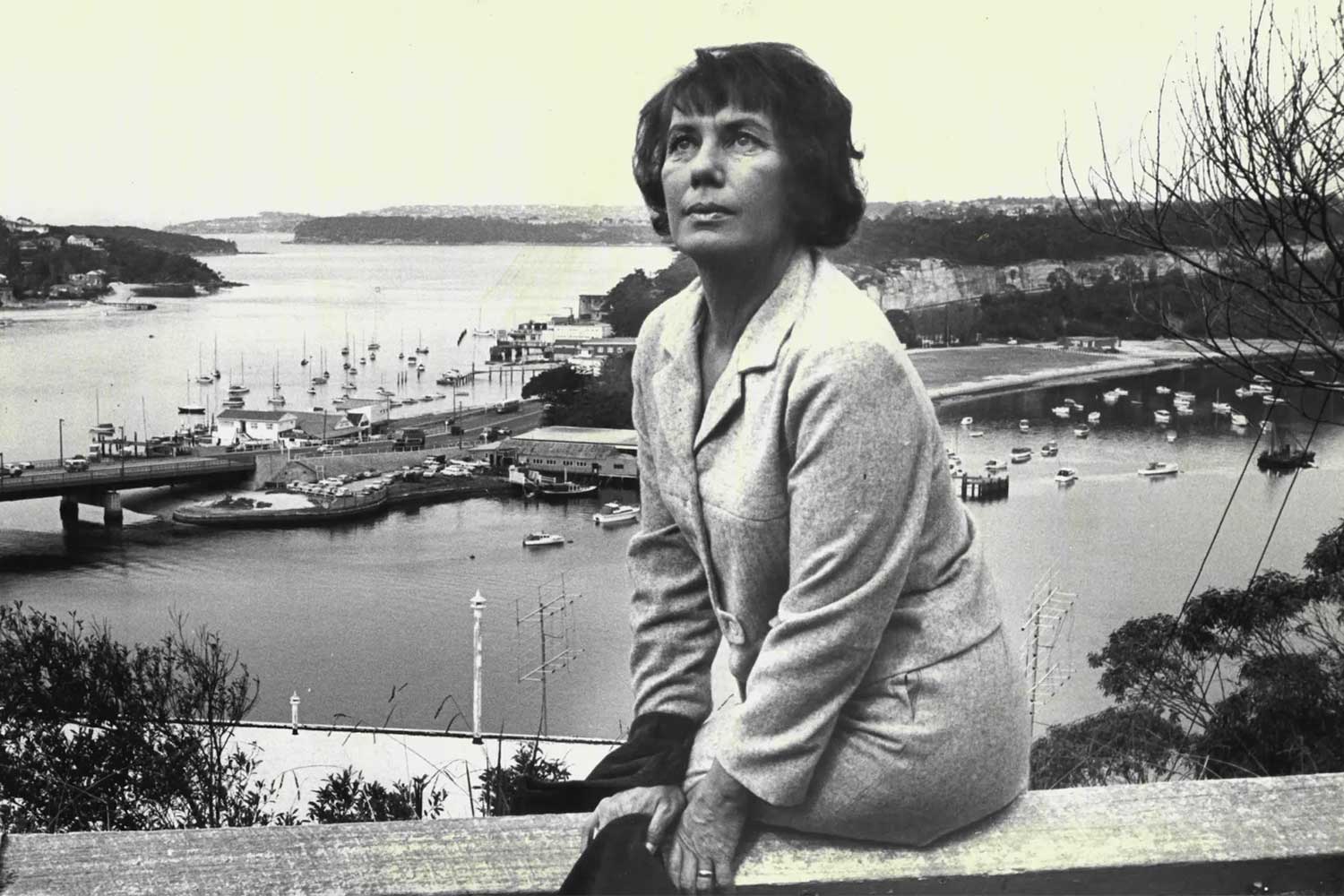

Flashback 1965: Australian author Charmian Clift on life in Neutral Bay.

Charmian Clift is remembered for her lyrical yet conversational prose style that became her trademark. Image: Sydney Morning Herald.

Charmian Clift was Australia’s foremost essayist of the 1960s, publishing over 200 pieces in The Sydney Morning Herald. She also published two travel memoirs, two novels and co-authored many others with husband George Johnston.

In 1964 Charmian returned to Australia with her family, after ten years living and writing on the Greek islands of Hydra and Kalymnos. In 1965 they rented a flat in Ben Boyd Road Neutral Bay, which inspired this essay, titled “Living in a Neighbourhood.”

It was published in The Sydney Morning Herald on 14 October 1965.

By CHARMIAN CLIFT

Practically every popular Greek song I know that doesn’t deal with the boy-girl bit, either straight or by way of little cypress trees or spring swallows or white ribbons or some other similar device, has as its subject, nostalgic and yearning, the neighbourhood.

No other neighbourhood is or ever can be the same as the one in which one grew up, or lives now, or will return to after exile, or grow old in, or whatever. No other people could be so friendly, no streets so gay, no corner tavern so lively, no music so enchanting, no girls so pretty, no friends so true. And like that. That is what the song ‘Never on Sunday’ is all about, whatever the simpering English version says, and when Melina Mercouri sings that song she is singing praise of the Piraeus and the harbour and the markets and the football team and the people in the streets and the sailors’ dives and her undying loyalty to all this, her neighbourhood, vibrant and squalid and spellbinding.

London, although rather more reticent about putting it to music, has something of that feeling too. Somebody once said that London is less a city than a series of villages, and if you live there for a while you do enter into an emotional relationship with your own village, which might be Chelsea or Soho or Pimlico or Notting Hill Gate or Mayfair or Rotherhithe or Putney or Limehouse or Bloomsbury or Hampstead. Each of these neighbourhoods has its own distinct personality and quality. Each is strongly individual, and its individuality partakes of the people who live in the neighbourhood plus the mixed flavours of its commercial amenities – the bookshops and the barrows and the bakeries and the fishmongers and the gentlemen’s hatters and the pubs and the tea shoppes and the espresso bars and the rooms to let and whether the landladies accept coloured gentlemen or not. A neighbourhood is nannies in a square and intense young students and gaudy chieftains in coffee bars and street-corner prophets hurling denunciations and loose ladies being asked to move on and successful actors being seen and decayed and slightly dotty gentlewomen pricing haddock and exquisite women emerging from converted mews to sweep away in silver Jags, and whether a neighbourhood is going down or going up it has a certain intensity in atmosphere and a coherence in spite of its fluidity. The street-corner prophet and the decrepit newsboy and the bird-watcher go on for ever, as does the pub philosopher who knew it when.

George Johnston and Charmian Clift at work in Sydney in 1948. Photograph: Clift Estate

I expect this is true of Australia too, or the urban part of it as distinct from the suburban, where I think it would be straining romanticism (even though elastic) just too far to expect anybody to be passionately attached to a service station or a drive-in or a supermarket or a chain store or even a bowling alley or a Leagues Club.

Having just moved into a neighbourhood (the first approximation of one I’ve lived in since I came back to Australia), I’ve been loitering about in it this last week or so, idling down streets, mooching in shops, listening in on conversations. Getting acquainted, as it were.

It seems to have a quirky sort of character. A blend of the raffish and the smart, a mixture which I, personally, find piquant and attractive.

Get The Latest News!

Don’t miss our top stories delivered FREE each Friday.

There are, naturally, the supermarket and the several service stations, which the neighbourhood wears with the air, at once desperately uncertain and desperately gallant, of somebody trying on a false hair-piece for the first time. The face-lift and the false eyelashes may follow, but there isn’t enough confidence for them as yet. The old family grocer is still in business, and many other old family businesses too. The haberdasher does not sell textured stockings, and I suspect never will, the florist makes up Victorian posies and also corsages of carnations or orchids, there is a tailor whose window is populated by very ancient dummies clad in tacked half-garments of uncertain period and who will carry out repair, make ladies’ costumes, or convert double-breasted suits into single, with the new narrow lapel. There are two dressmakers who both create formal wear, ladies’ own material made up (or created). There is ironmongery and carpentry and shoe-repairing and laundry and electrical goods, and there are a surprising number of other old family businesses boarded up and looking desolate and flyblown, in limbo as it were, until their metamorphosis into smart boutique or pricy antique shop.

There are lots of those, and interior decorators, and glittering pharmacies and purple-draped hairdressing establishments specializing in colour rinses and wiglets, but there are also terribly exciting and cluttered junk shops and an auctioneer’s saleroom which is a treasure trove of ancestral discards and very jolly and hectic on auctioneering days. Every greengrocer’s and every milk-bar is attended by quick and voluble Latins with eyes the colour of Kalamata olives, and there are innumerable delicatessen aromatic with mysterious bundles of sausages and fragrant with cheeses and lovely bread smells and positively vibrating with the hum of foreign conversations, which lack restraint. There are two Chinese restaurants, with take-away meals, which should be very convenient while I am still apprehensive about using my science-fiction electric cooker, and a Spanish one that looks too smart to just drop in on. There is a Polish furniture-maker who is a real craftsman, and a folk-singing joint for my adolescent young, and a music-hall where I can’t afford to go, and a butcher’s shop where, to my astonishment and delight, I was served by somebody I went to school with, all dressed up in a blue apron and looking most unlikely.

Then there is a gunsmith whose shop is pure James Bond and who covets my eighteenth-century pistols which I acquired a little dubiously and have entrusted to him for cleaning, and where I have a discreditable but intolerably heady urge to go and practise target shooting. This is closely linked to the wistfulness I feel wandering around the second-hand car dealer’s among all the low-slung beauties of decent vintage that I have never owned and have secretly yearned for as much as everybody else with a feeling for style. Perhaps, in this life, one should cultivate frivolity as well as endurance.

Charmian Clift in Sydney in 1964. Image: Sydney Morning Herald.

And there is the corner pub. Not just a corner pub, although it looks conventionally hideous enough on its street sides. But behind it there is a garden with tables and benches and geraniums blazing away and a wonderful oak-tree and it is just about the most civilized public place I’ve found in a year and I shall have a lot of pleasure there sitting in the sun at a slatted table peeling its paint and drinking very cold beer and making out shopping lists and watching the regulars come and go.

Because the neighbourhood is its inhabitants too, and these are colourful, mixed, not easily slotted into one category. There are the housewives, stopping by to meet after a morning’s shopping, and there are the self-conscious weekend customers in carefully careless informal wear with the right accessories of poodles or bull terriers, there are workmen in overalls and foreign wanderers carrying airline bags and nervously suspicious expressions. There are the beautiful young, not yet in one another’s arms but working up to it, and there are the oldest of the regulars, stubborn, isolated, and resentful, who knew it when.

There is also, in my street, an old brick cottage with two peppercorn trees in front and a rocking horse on the verandah, and further down there are four small children who say hello to me now as I pass by.

All in all, I have the feeling that I am living in a neighbourhood.

Get The Latest News!

Don’t miss our top stories delivered FREE each Friday.