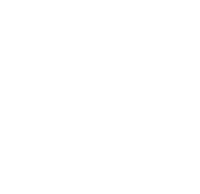

Local History: 100 years ago, Clifton Gardens was the site of Sydney’s most popular hotel.

Mosman Collective writer MICK ROBERTS has travelled back more than a century, to reveal the fascinating history behind former Sydney landmark, the Clifton Gardens Hotel.

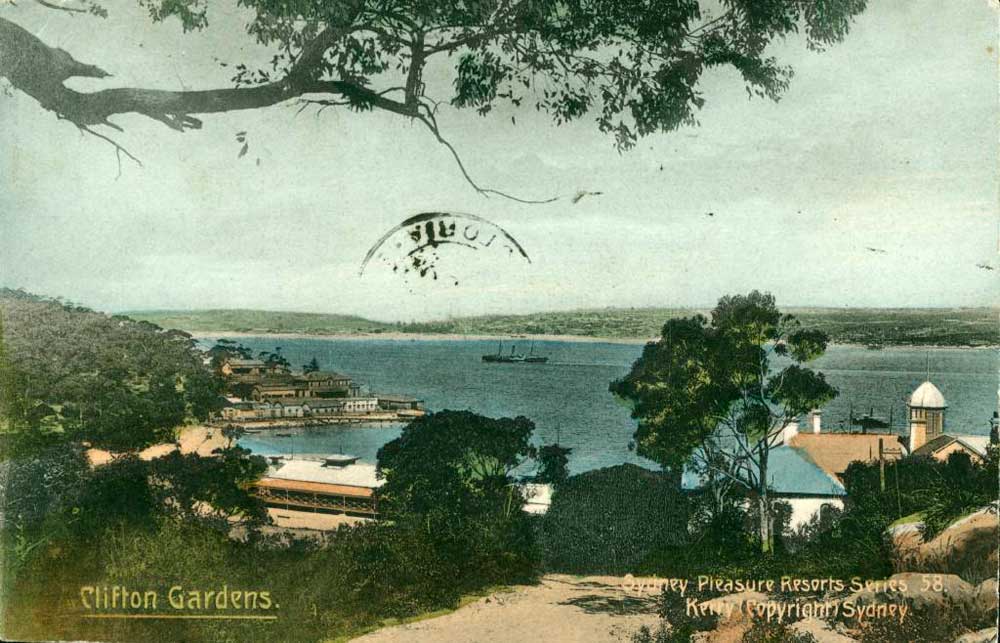

For just short of a century, nestled in a wooded amphitheatre overlooking Sydney Harbour, once traded arguably one of the city’s most famous tourist destinations.

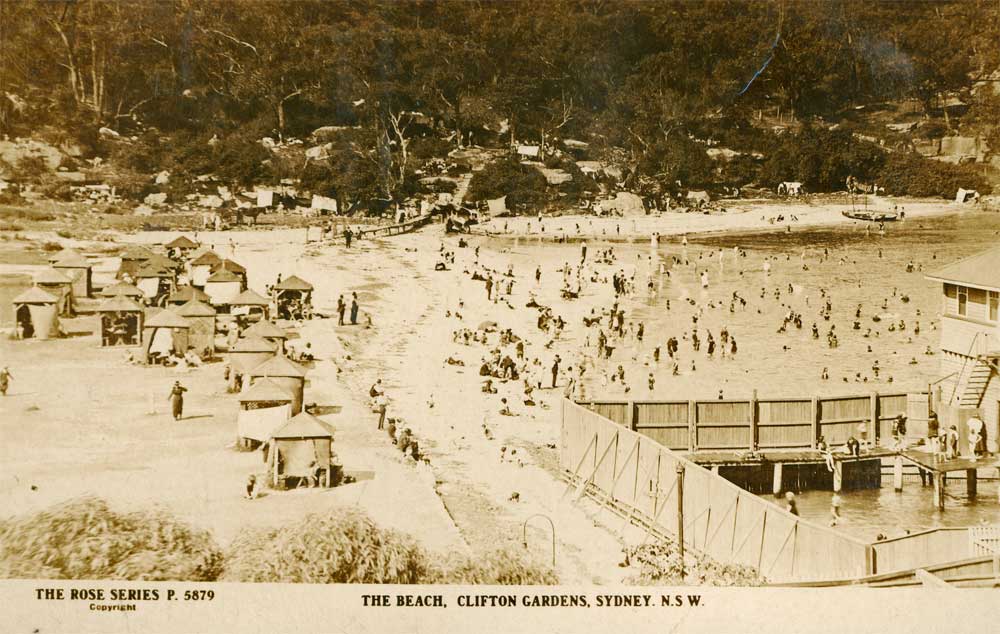

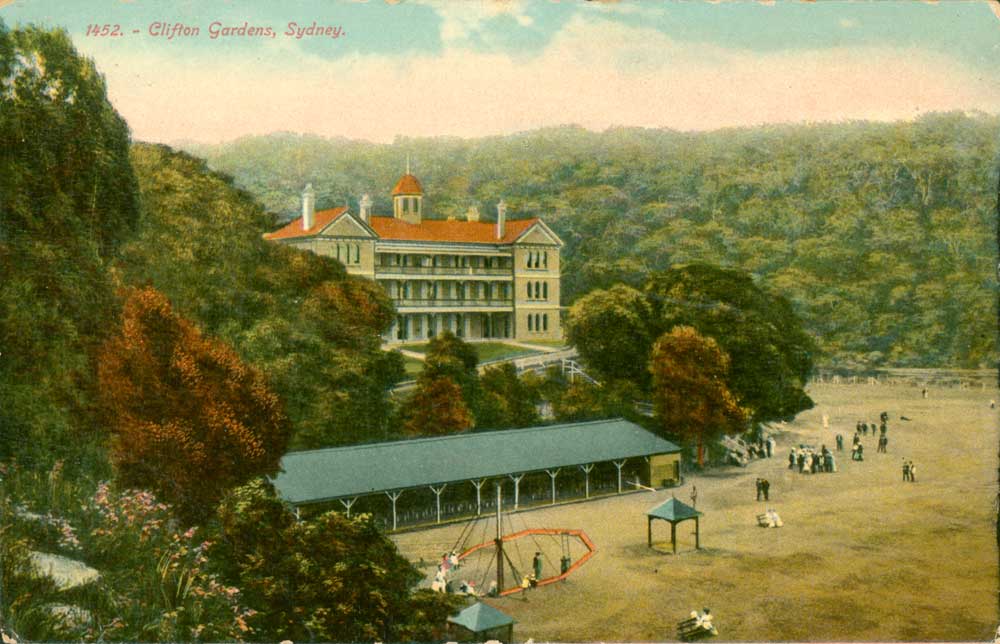

The Clifton Gardens Hotel – within easy reach of a rapidly growing and crowded city – was surrounded by picnic grounds, bush walks, dancing pavilions, and in later years a scenic railway and netted harbour swimming pool.

It became a favourite weekend leisure spot for colonial Sydney.

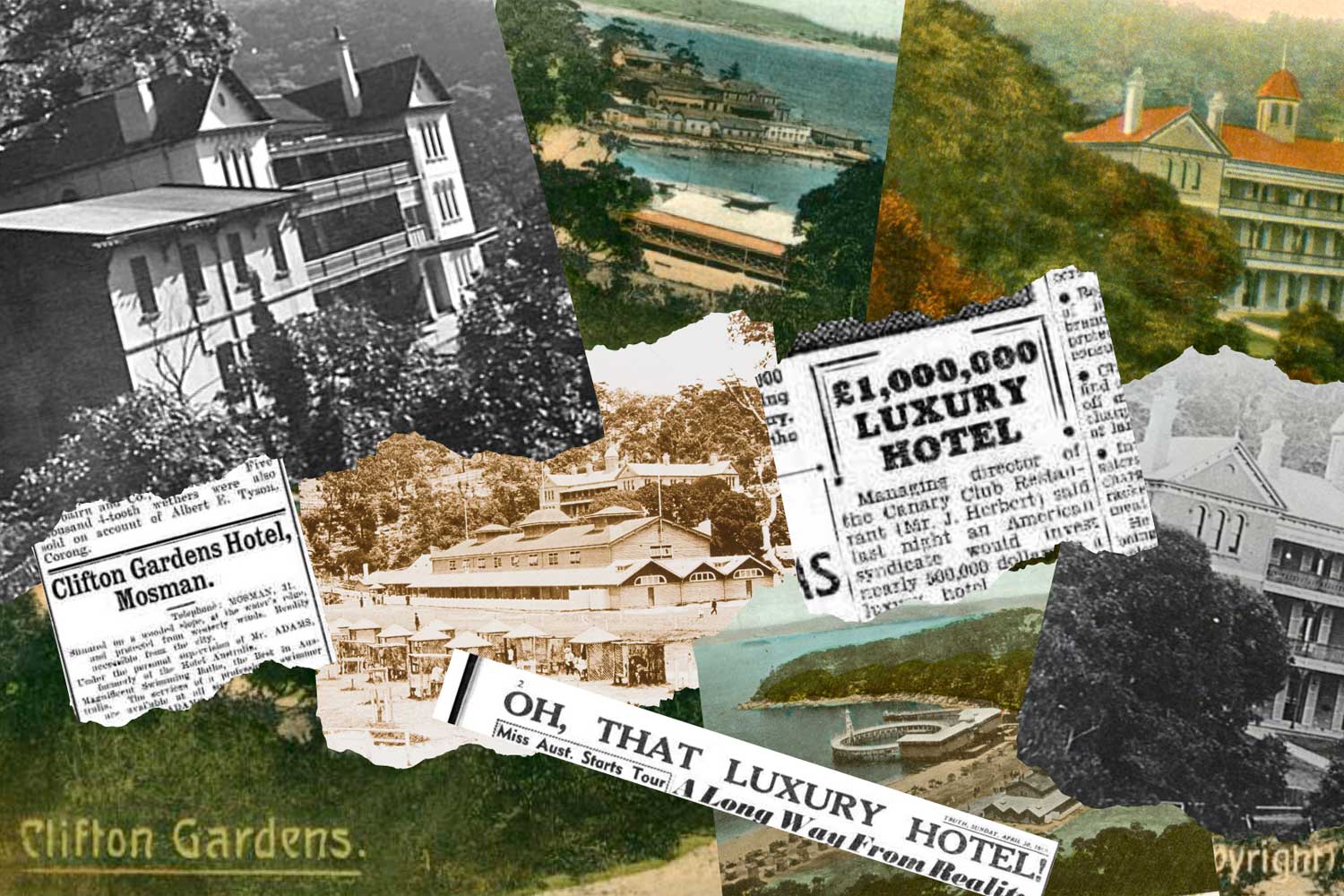

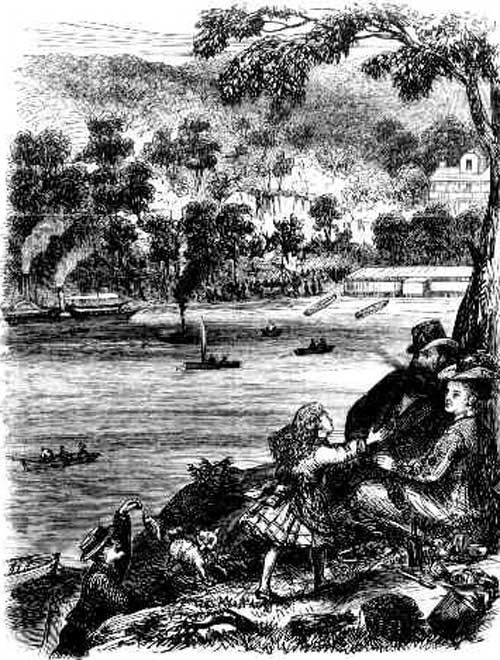

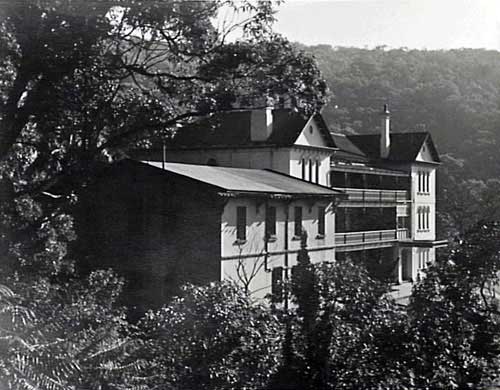

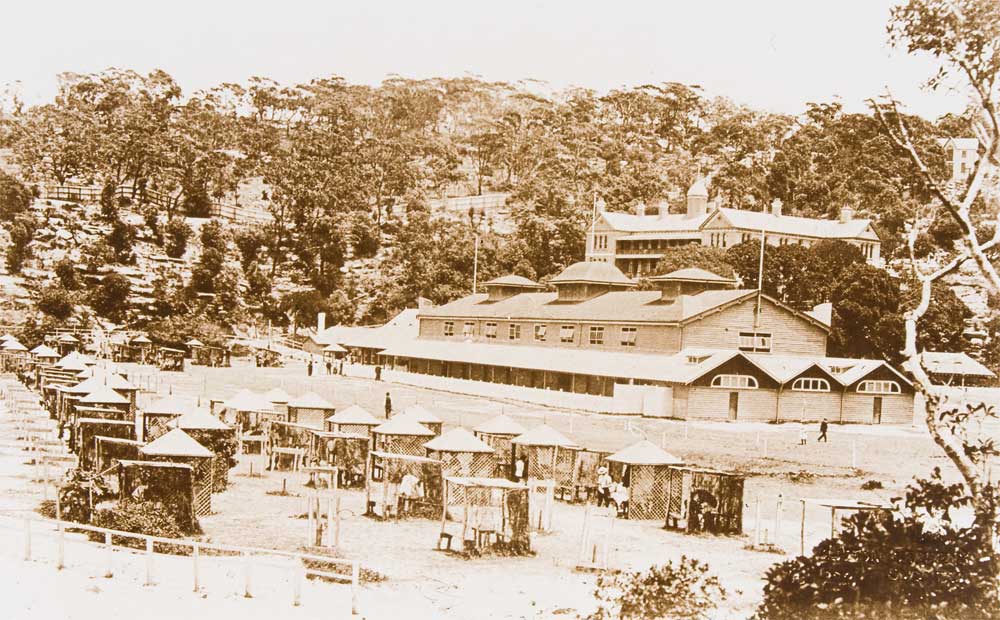

Clifton Gardens Hotel. Image: Illustrated Sydney News 18 February 1871.

Pleasure resorts, with their dance halls and picnic pavilions, were a big part of the city’s social life in the Victorian era. Serviced by city ferries, they had existed on the harbour since the 1850s, and hit their peak in popularity at the turn of last century.

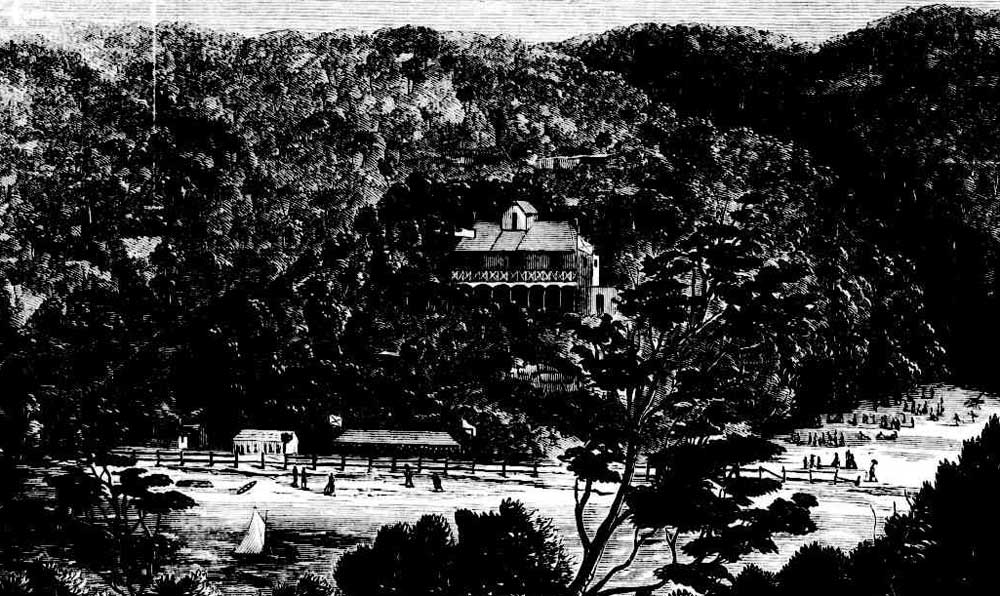

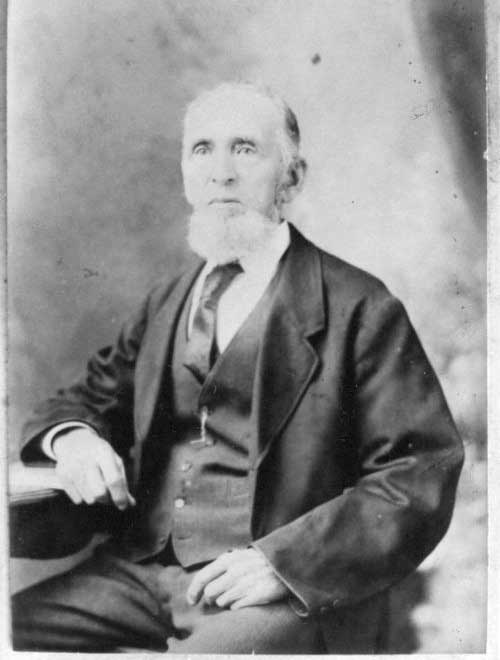

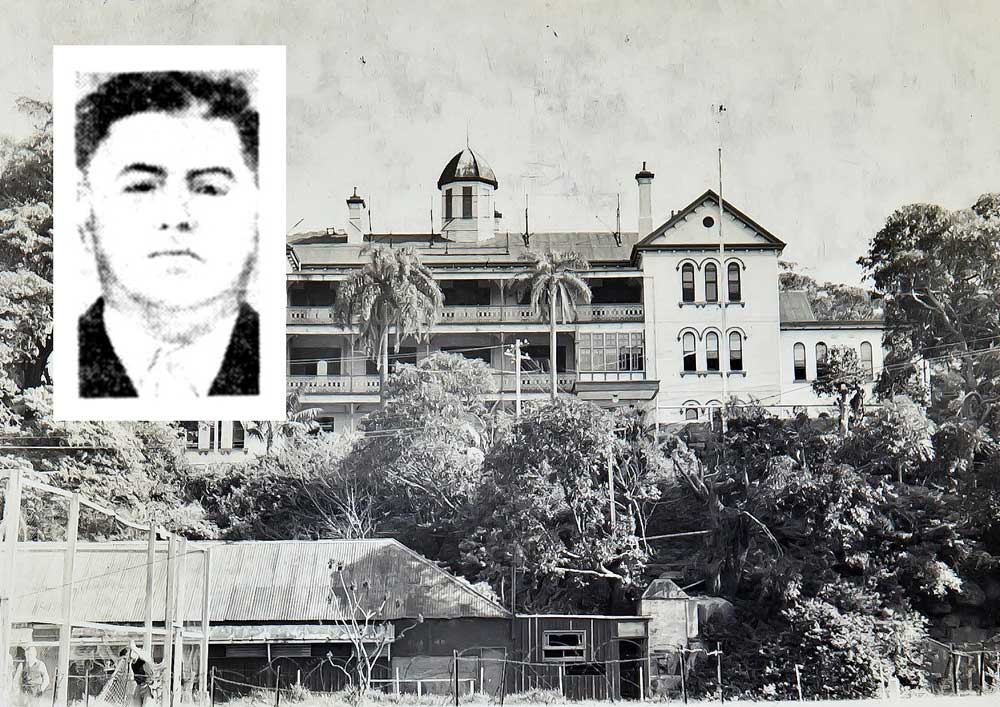

Clifton Hotel. Illustrated Sydney News 18 February 1871 with inset Duncan Butters.

In 1871, a hotel was established at the Chowder Bay picnic grounds by Duncan and Mary Butters.

A shipwright and carpenter by trade, Butters wasted no time transforming the site into a spectacular family wonderland. He built a huge dance hall and was granted a hotel license for an existing two-storey stone house originally built by Captain Edmund Harrison Cliffe.

Describing the popular picnic destinations on Sydney Harbour, the Illustrated Sydney News reported on Saturday 18 February 1871 that “the enterprise of those who cater for public enjoyment is continually developing new spots of scenery to gratify the tastes of those who are best pleased with novelty”.

The newspaper, with a picture of Butters’ new hotel, described Chowder Bay as Sydney’s newest attraction, offering “all kinds of active amusement, while its diversity of rock and woodland is acceptable to those whose enjoyment is of a less exuberant character”.

For five years, the publican and his family enjoyed a quiet and idyllic life at Chowder Bay, except for an incident reported in 1874 when three dozen bottles of ale and porter, valued at 42 shillings, were stolen from the hotel.

The following year, Butters became a widower with the death of his wife, Mary Anne, from a “painful inflammation of the lungs, at the hotel. She was just 32 years of age.

Mary’s death left Butters with six children, including a new-born with the eldest aged 14.

Butters remarried 25-year-old Elizabeth Dicey in 1878. Elizabeth was reportedly the nurse of Butter’s departed wife.

He then sold the lease, license and goodwill of the Clifton Hotel and grounds to David Thompson in 1879, after suffering financial difficulties from poor weather and high fixed costs running the Chowder Bay Pleasure Grounds. This included entertainment costs and subsidising ferries from Circular Quay. He was declared bankrupt and sold the lease at a discount price to ferry owner Captain David Thompson to cover the debt.

At the time, the hotel contained 10 rooms, with “a large bar” and a detached kitchen.

On the grounds was a large dining pavilion, 148 feet (45 metres) long and 25 feet wide (seven metres); also, a two-storey building used for luncheons and teas.

The grounds featured a “first-class pavilion” for dancing, fruit stalls, and summer houses. An advertisement from the time also revealed that steamers could land passengers at all tides on a wharf in the bay.

After leaving the hotel, Butters was licensee of the Sir John Young Hotel at 557 George Street, Sydney from 1879 to 1882. He was also licensee of the Figtree Recreation Ground at Hunters Hill from 1882 to 1885 before returning to his old trade as a shipwright.

The founder of the Clifton Gardens hotel died a widower, after losing his second wife, at the age of 85 in 1906, leaving nine grown-up children.

The new hosts of the Clifton Hotel, David, and Mary Thompson were an Irish couple, who had married in Sydney in 1863.

David and Mary, both in their mid 40s, moved into the Clifton Hotel, with their five children, aged from six to 16, in 1879.

A well-known sea captain, Thompson oversaw several vessels, transporting goods and passengers along the east-coast of Australia between Melbourne and Newcastle. He also owned a Sydney ferry.

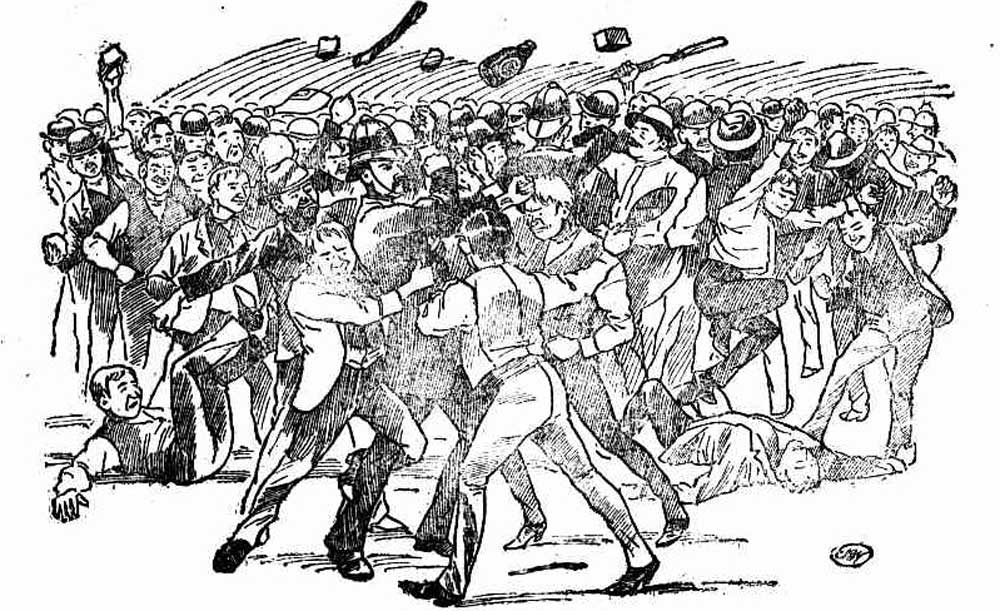

The Thompsons took control of what was then known as the Clifton Arms Hotel during a notorious era when criminal gangs, known as ‘The Push’, were running rampant across Sydney in the 1880’s.

Harbour picnic grounds, including Chowder Bay, became their favourite battle grounds, with rival groups fighting at the secluded grounds, often involving police.

The remote location meant Thompson struggled to maintain order on his own and in June 1883, he was refused a license renewal thanks to constant drunk and disorderly patron behaviour.

Determined to reopen, The Sydney Morning Herald reported in July 1884 that after “some little discussion” and a petition calling for the hotel to remain, the Bench granted Thompson a new license for the Clifton Hotel.

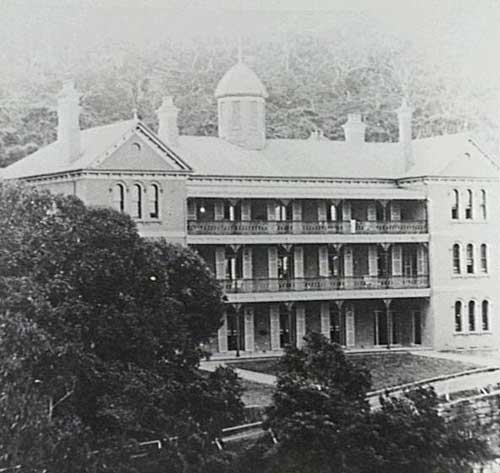

He immediately went to work, redeveloping the old hotel, extending the wharf, and adding a skating rink, plus a new pavilion. Importantly, he also gave it a new name and in August 1885, the 40 room Marine Hotel opened (which had cost £15,000) opened to a new class of clientele.

The days of rowdy behaviour at Chowder Bay, with heavy drinking and fighting, had been finally put to rest.

Standing three-storey’s high, the imposing public house boasted a 35m frontage and uninterrupted views of Sydney Harbour.

Inside, overnight guests could enjoy hot and cold-water baths, and the “most modern devices for securing the best sanitary and ventilating effects”. Exclusive of the rooms for general use, there were 45 apartments, “furnished with great taste and liberality”.

Thompson’s “handsome new pavilion” accommodated 5,000 people, and the publican imported a bathing machine from England, “by means of which visitors may enjoy a bath in the sea with perfect security and without fear of sharks”.

The ingenious contraption worked by being wheeled out to the water, where a frame was lowered down and the bather, completely enclosed, was “as safe as in a plunge bath in his own home.”

The pavilion was constructed of wood and iron and was 200 feet (60 metres) long by 40 feet (12 metres) wide, with a height of 30 feet (9 metres) elevation and was supplied with a refreshment room at the entrance for the convenience of visitors.

Steamers ran regularly to Clifton Gardens from Circular Quay, and Thompson’s new business venture was an immediate success, with the Marine Hotel and pleasure grounds quickly becoming one of Sydney’s most popular and respectable resorts.

The Marine Hotel fast became a favoured destination for honeymooners, family gatherings and visitors from all corners of Australia. Captain Thompson, as he was widely known, remained licensee of the Marine Hotel until 1896 when, at the age of 61, he transferred the license to his 22-year-old son, Alexander.

The old skipper died at the hotel he built overlooking Sydney Harbour on July 25, 1900, at the age of 65, leaving his wife Mary, and four adult children.

Mary Thompson, born Ireland died Clifton Garden, Sydney 1905: Family Genealogy website.

Captain Thompson’s widow took over the license of the Marine Hotel from her son in April 1901 at the age of 66.

She remained as host until her death aged 70, in 1905. Mary was laid to rest beside her husband in the Gore Hill Cemetery at St Leonards.

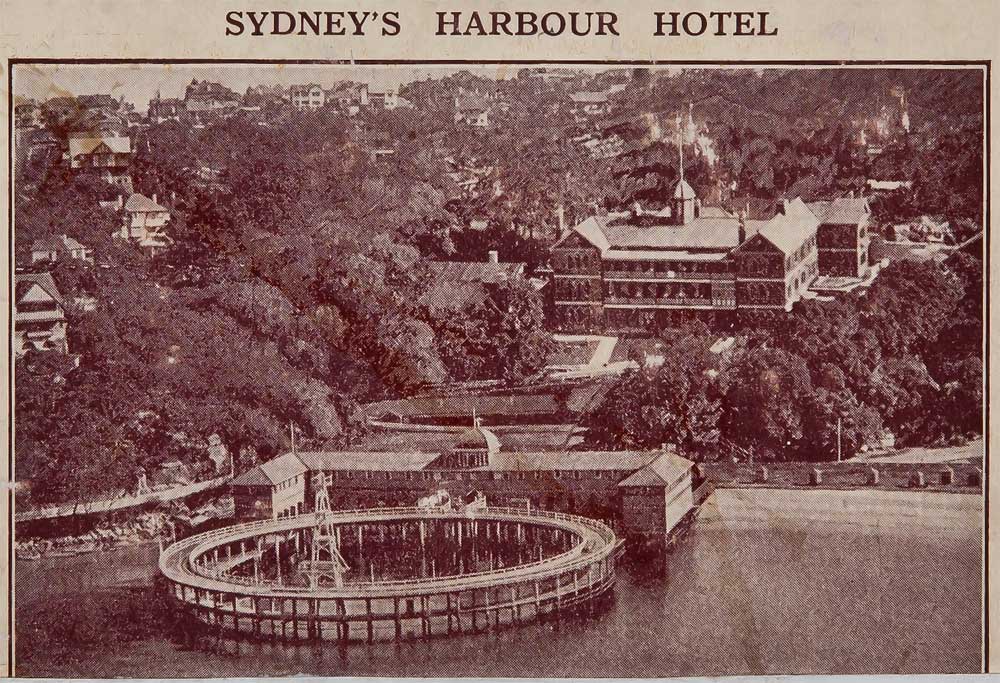

In 1906, Sydney Ferries Limited purchased the Thompson estate comprising land, the three-storey hotel, wharf, dancing pavilion and skating rink. The sign of the hotel was officially changed from the Marine to the Clifton Gardens Hotel with the new ownership.

The company built a large circular swimming enclosure which could hold 3,000 spectators, a boatshed, and a tramway from the wharf to the hotel.

Mary Thompson, born Ireland died Clifton Garden, Sydney 1905: Family Genealogy website.

However, by the 1930s the Clifton gardens had seen its best days. The opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge and the popularity of the motor car allowed Sydneysiders to venture further into the countryside for leisure activities.

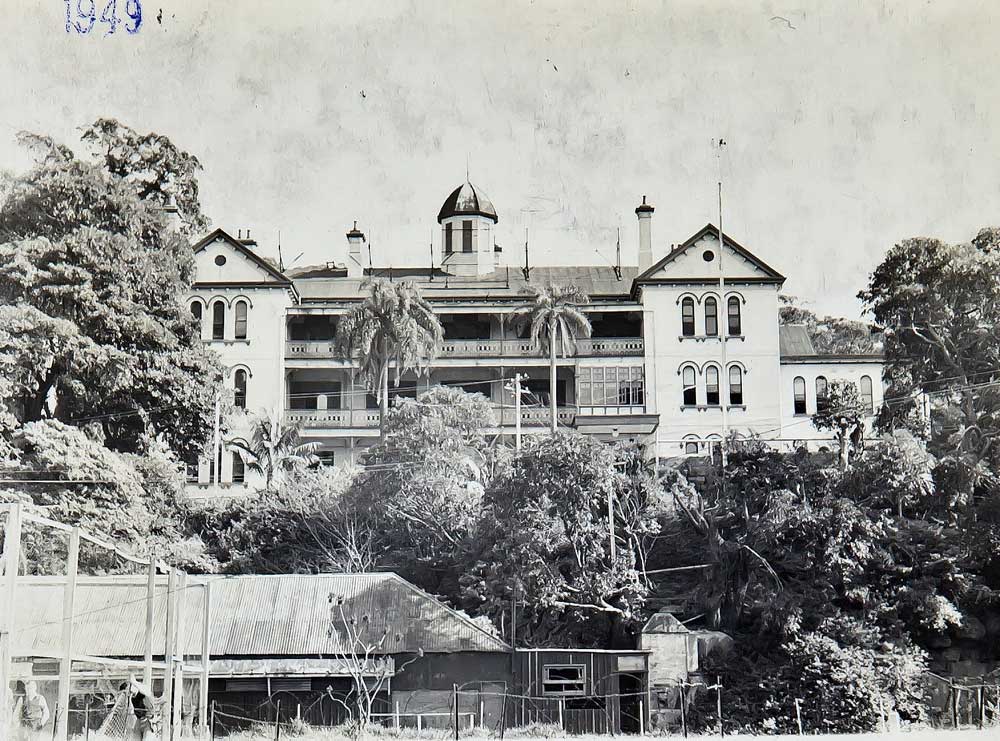

Sydney Ferries sold the hotel and surrounding five acres of land to Canadian-born, Sydney entrepreneur Joseph Lionel Herbert, owner of Sydney’s Canary Club in 1949.

Herbert, 48, had been a caterer, a restaurateur, and a dance hall proprietor in Brisbane, before making his way to Sydney where he operated the Canary Club Restaurant. Herbert became licensee of the Clifton Gardens Hotel in 1950.

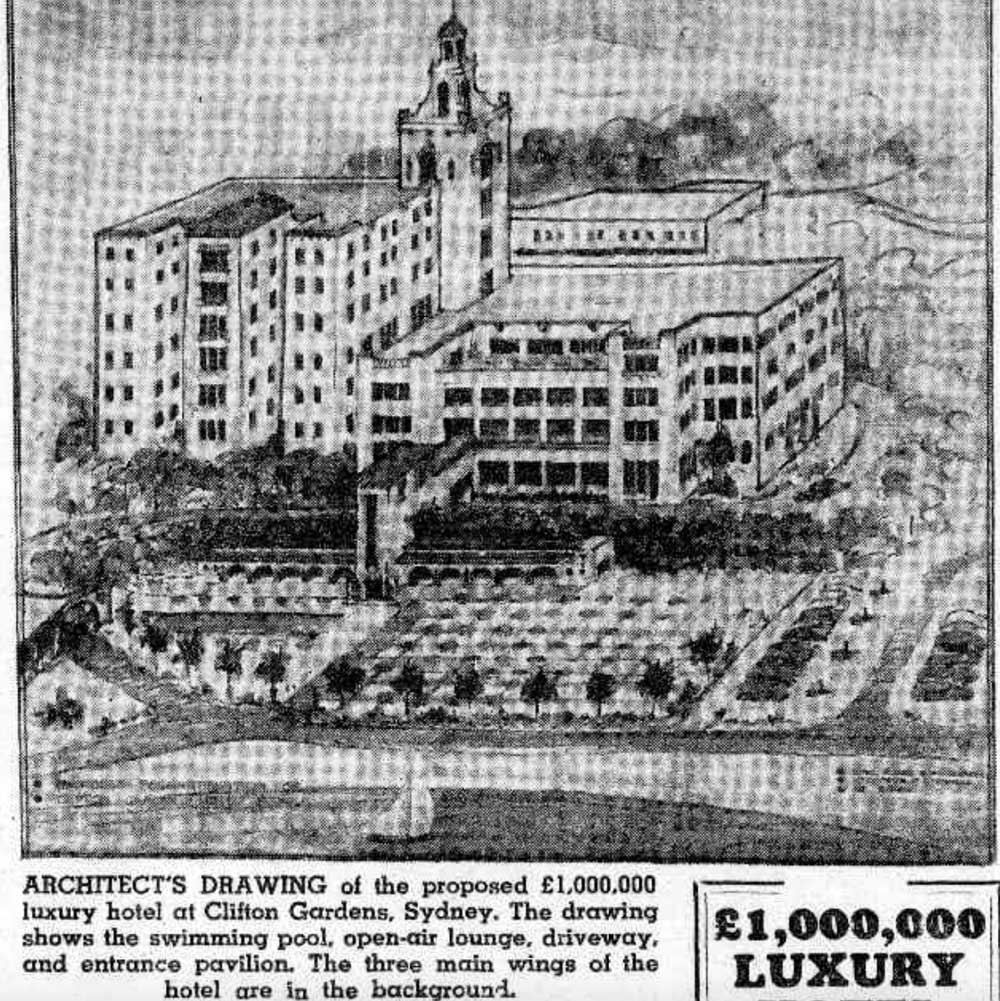

Like Thompson had 70 years before, Herbert had grand plans for the site. He floated a company to replace the existing hotel with a £1,000,000 luxury hotel to feature a beer garden, ballroom, swimming pool, shopping area, kindergarten, chapel, and car parking. The hotel would also boast hairdressers, chiropodists, dry-cleaners, and launderers, plus its own private police force!

Not surprisingly, there was a public outcry to the plan, and the NSW Trades and Labour Council lobbied the State Government and Mosman Council to prevent the sale of Clifton Gardens waterfront reserve to the Canary Club, and instead return the property to public ownership as a reserve.

Herbert’s plans reportedly collapsed when he and his backers couldn’t get permission to redevelop the site. The Daily Telegraph reported on January 24, 1952, that Herbert was “a sad and sorry man — with the five and a half acres of land tied up in a mass of red tape”.

A disappointed Herbert sold the property to James William Taylor, owner of the Commercial Hotel at Warialda in 1956 – the same year the landmark pavilion was destroyed by fire.

By the 1960s all the resort structures at the gardens had been demolished except the shark-proof swimming pool. In 1965 the hotel closed and was sadly demolished on November 17, 1967.

The owner had plans for a residential development of the site, but Mosman Council refused permission, and the site was purchased for inclusion into the Clifton Gardens Reserve.

In the 1970s Clifton Reserve was re-landscaped and virtually all remaining pleasure ground era structures demolished.

Get The Latest News!

Don’t miss our top stories delivered FREE each Friday.