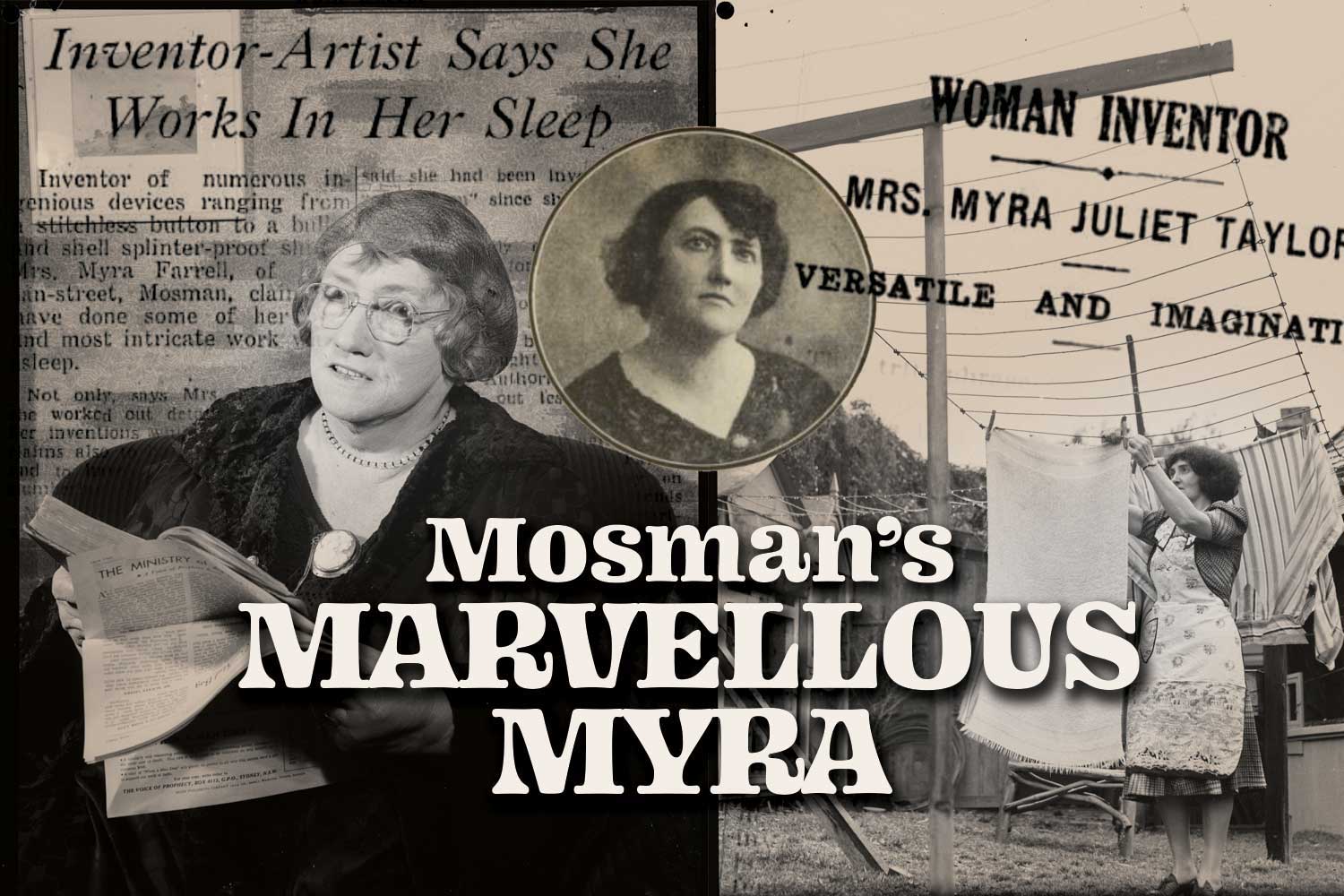

Myra Taylor-Farrell: The “odd duck” Mosman mum who became Australia’s most prolific female inventor.

By KATHRYN BARTON

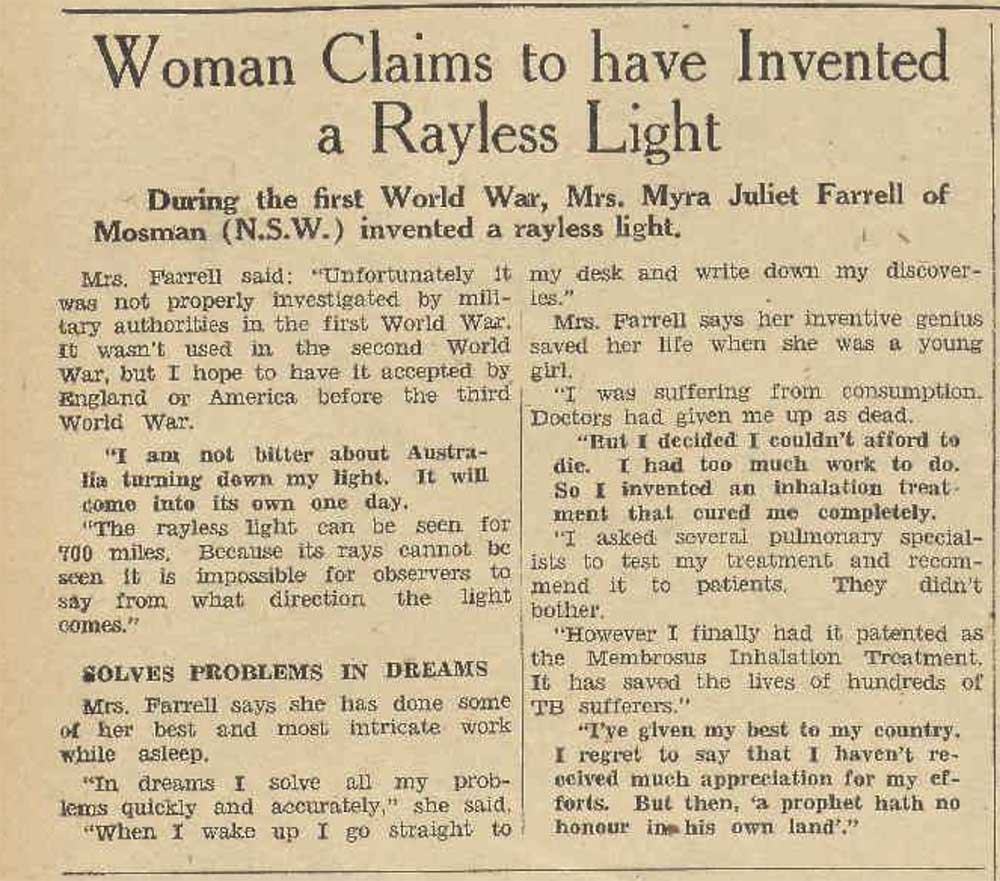

It was Australia’s entry into WWI that saw a young widow, Myra Taylor, brace herself as she stood at North Head on a windy night in 1915. There she tested her rayless, light-throwing device to see if it might benefit the Allies.

She hoped its reach was impressive, but there was no way for her to measure the distance. The unnamed light had no tell-tale beam to betray its source.

Reports soon reached Mrs Taylor that the light had confused the crew aboard a ship some 700 miles – 1,127 kilometres – out to sea. The alarmed captain had contacted the lighthouse keeper at South Head to ascertain what was happening. He was none the wiser.

Myra Taylor (later Farrell) was a Mosman resident who became one of Australia’s most prolific inventors.

Speculation grew, but the kerfuffle abruptly ended when the Department of Defence, newly thrown into the world war arena and interested in the device, simply confiscated the plans and prototype.

Unbelievably, the disappointment was just a blip for Mrs Taylor, who was busy filing patents for inventions to ease soldiers’ daily discomfort, give medics a superior way to bind wounds, and a new method of mitigating frontline injury and death.

The blatant confiscation, or theft, of her work would become a theme for Mrs Taylor, but this was not her most significant stumbling block. She was dismissed as a barely educated, weird little woman who tinkered away in a shed filled with chemicals and all manner of things from which she produced the stuff of dreams. Literally.

Myra’s “Rayless Light” invention was said to have travelled 700 miles in 1915. It was rejected by the Australian Defence Department.

Sleep on it.

As a child, Myra Taylor was markedly different from her peers. Never knowing it had a name, she had a rare neurological condition called somnambulant writing. It allowed her to focus on an idea as she slipped into sleep and had an invention developed or problem solved by morning.

While still asleep, she’d get out of bed and feverishly record her ideas on anything suitable, including walls and bedsheets. Her scrawling included complex maths solutions, technical drawings, specifications, and detailed prototype plans. Add to this a shopping list, and she was done.

However, by morning she needed a mirror to decipher the lot. She had written the words backwards, starting her notes from the right-hand side of the surface.

“Rifle, shell, and machine-gun proof.”

Mrs Taylor’s next invention attracted even more attention. Her Defence Fence had survived the lengthy assessment process, from thousands of culled entries, following the department’s public shout-out for ideas.

The Defence Fence consisted of two steel shields with sturdy, coiled springs wedged and welded between them. The department pronounced it “rifle, shell, and machine-gun proof”. Despite the lofty endorsement and resultant media, it was confiscated.

It seemed the ‘M J Taylor’ on the application was female, seen as an odd duck, at least in the eyes of the war cabinet.

Myra had more luck with her “stitch-less button”, known as the press-stud today, and her “stitch-less hook and eye”, which allowed soldiers to rapidly don and doff the now pull-apart fronts of their khakis. So, the department was happy with Mrs Taylor’s inventions as long as she stayed in her lane and did not veer into engineering traffic.

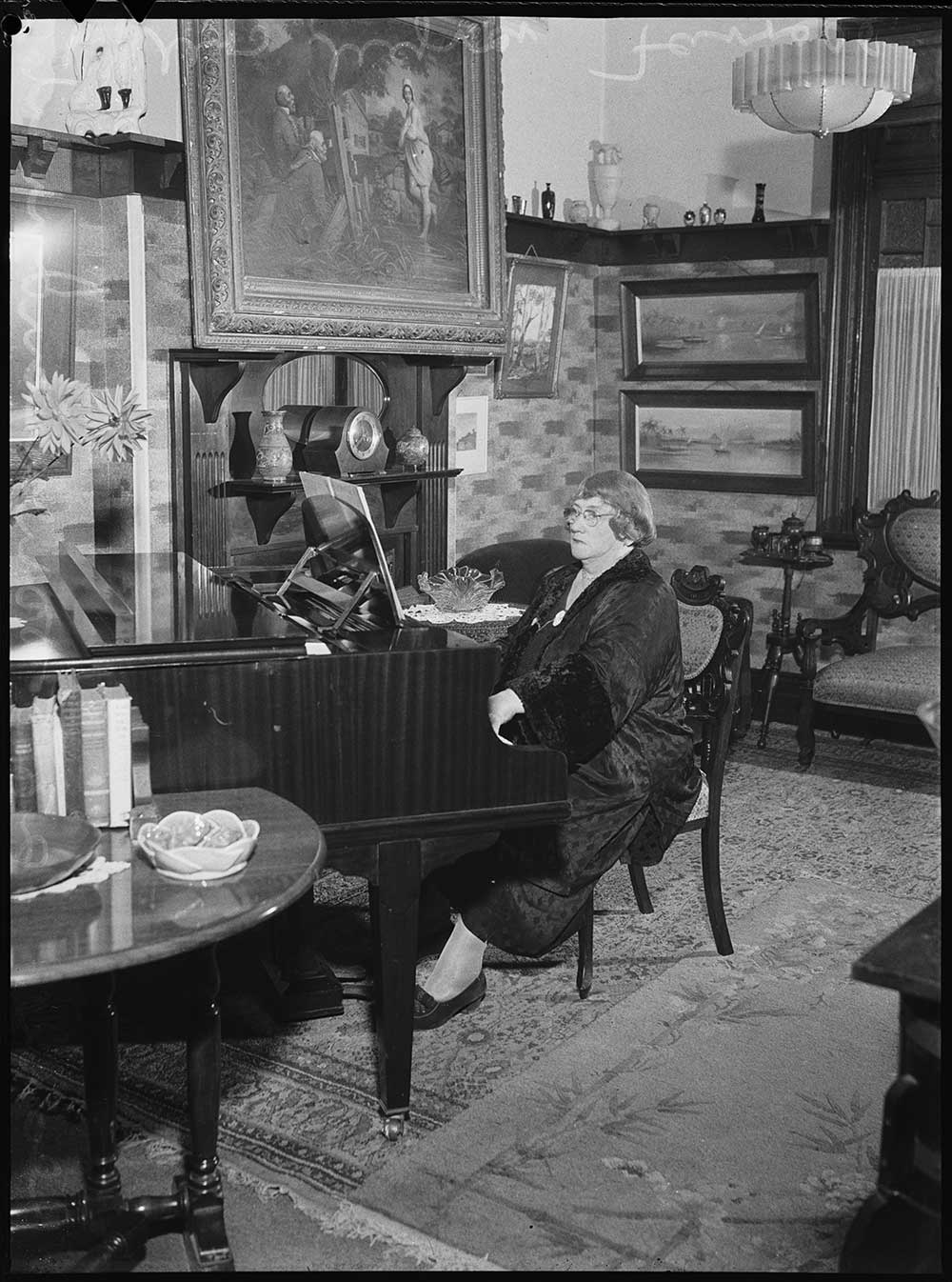

Myra Taylor-Farrell, photographed here in later life, was seen as an “odd duck” by many, despite inventing scores of life-changing gadgets that are used today.

Early life.

Maria Julia Welsh was born in County Cork, Ireland, to a clergyman, Marcus, and the daughter of an Australian engineer, Harriett, though some reports cite Mrs Welsh as the engineer.

Her father met and married her Australian mother in New Zealand; the newlyweds returned to Ireland, later losing their house to arson. Not long after, the family took an arduous trip by ship to Adelaide in 1880 when Myra was two years old.

Myra emigrated to Australia from Ireland in 1880, with her family settling in Broken Hill.

Following disembarkation, the Welshes quickly learned that silver had been discovered at Broken Hill. The Welshes, bringing religion to the area, set up camp in the mining town. They opened St Peter’s School in nearby Silverton, where six Welsh children were eventually educated.

At age 10, Myra startled her mother with her first invention, the self-locking safety pin.

Seeing her mother’s reaction, Myra joyfully pronounced: “I can do something that you cannot do!” Sadly, no one thought to patent the ingenious device, the forerunner to those in household drawers today. Later, in what must have been an arresting Deja Vu moment for Myra, her five-year-old also presented her mother with a prototype. The little girl was unhappy that her dolls never looked comfortable, no matter how she laid them out.

Death sentence rejected.

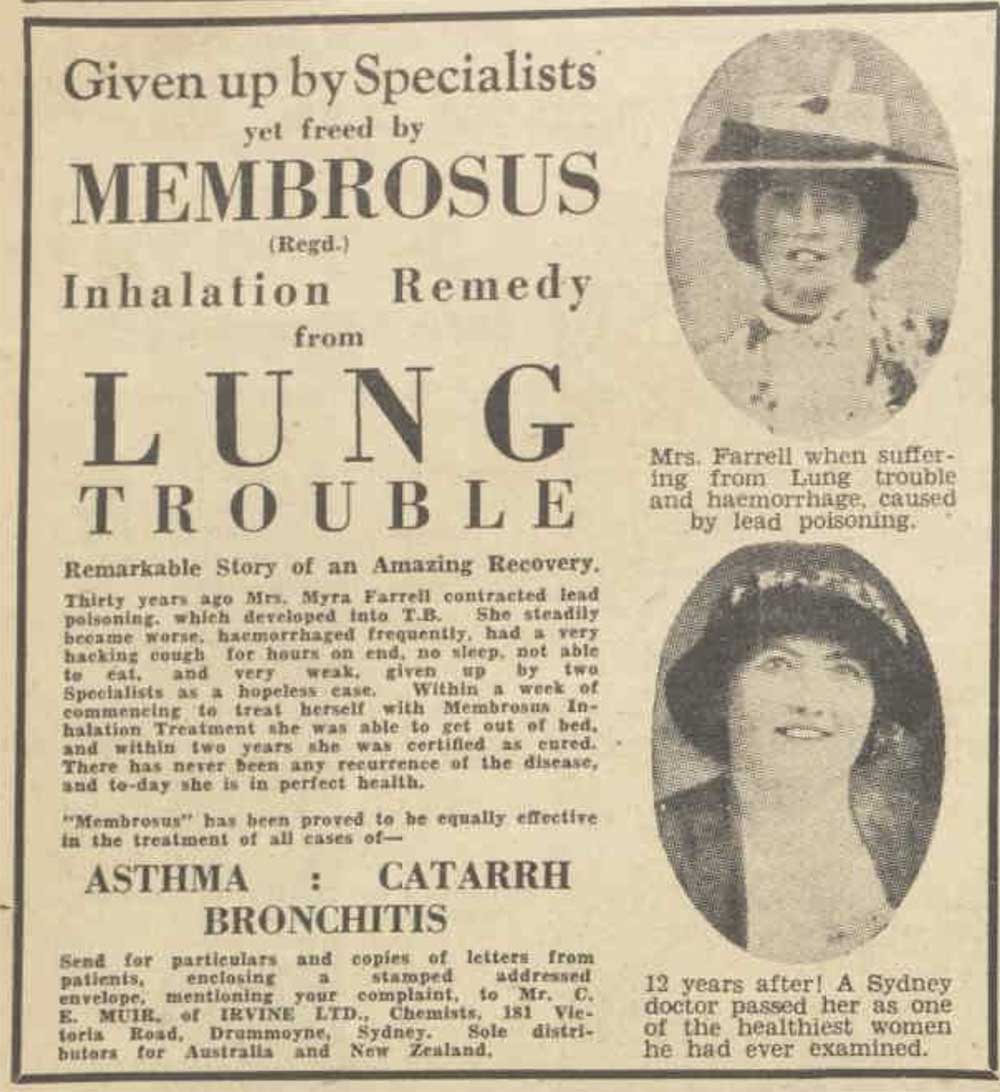

As a young woman, and likely due to the family’s proximity to the mines, Myra contracted lead poisoning. She slowly became bedbound and gravely ill after the poison had reached her lungs. Her parents took her to a specialist in Adelaide, whose prognosis was dire.

But Myra rejected the assessment, developing an inhalation system – a type of nebuliser – still seen in hospitals today. Her plan included an apparatus to clarify seven secret ingredients that, when combined in various prescriptions, forced into tablet form, and then burned, its fumes would clear the mucus, kill bacteria, and clean and heal the lungs.

An advertisement for Myra’s Membrosus Treatment, which became hugely popular as a treatment for Tuberculosis in the 1920’s.

Within a week, she was able to dress. Within three years, she was pronounced cured. Myra’s generosity and devotion to humanity were evident as she began her regular train trips to Victoria Hospital and Sanatorium in the Blue Mountains to treat desperately ill patients with her Membrosus Inhalation Treatment. For years she was inundated with letters from grateful patients.

At the time, she could not have known that her device was yet to become even more personal.

The dying Scotsman.

1905 was a big year for Myra Welsh. She had registered one patent, designed new devices, or improved others’ inventions, and had met a young Scotsman, William Taylor. Her soon-to-be fiancé was already showing signs of tuberculosis, or consumption, as it was called.

Doctors gave Mr Taylor three months to live not long after the pair met. Resurrecting her treatment, Miss Welsh began intensively nursing him. He had shown significant improvement within a year, and they were married.

2 Cowles Rd. Myra’s first home in Mosman. She later moved to Prince Albert St.

The Taylors lived at 2 Cowles Road, Mosman, and had two children, Lavie Curtis and William Paterson Welsh. During Mr Taylor’s illness, a three-month-old Lavie contracted the disease. Her mother altered the baby’s prescription, then administered the discrete formulas to both patients. Later, X-rays showed no sign Lavie had ever been so afflicted.

Mr Taylor died in 1912, seven years after they met. His wife had gifted him two children and much more time. By now, it had been mainly Mrs Taylor’s patents, licences, and royalties that had kept the family financially stable.

After her husband’s death, the Taylors moved to Perth, Bondi, Paddington, and then back to Mosman, settling at 27 Prince Albert Street.

The music man.

In 1919, Mrs Taylor, aged 41, married William George Farrell – an accomplished musician and director of the Empress Orchestra in the city. The couple had a son the following year: the much-lauded, child-prodigy violinist George Welsh Farrell, who at age 14 made his debut at a Sydney Town Hall concert in 1935, launching an impressive career.

Myra’s son, George Welsh Farrell, was a music prodigy who made his solo Violin debut at Sydney Town Hall aged just 14.

Twenty-four patents by 1915.

With WWI still raging, the female workforce ballooned as women took on roles such as munitions factory workers, farmers, administrators, firefighters, tram conductors, and more.

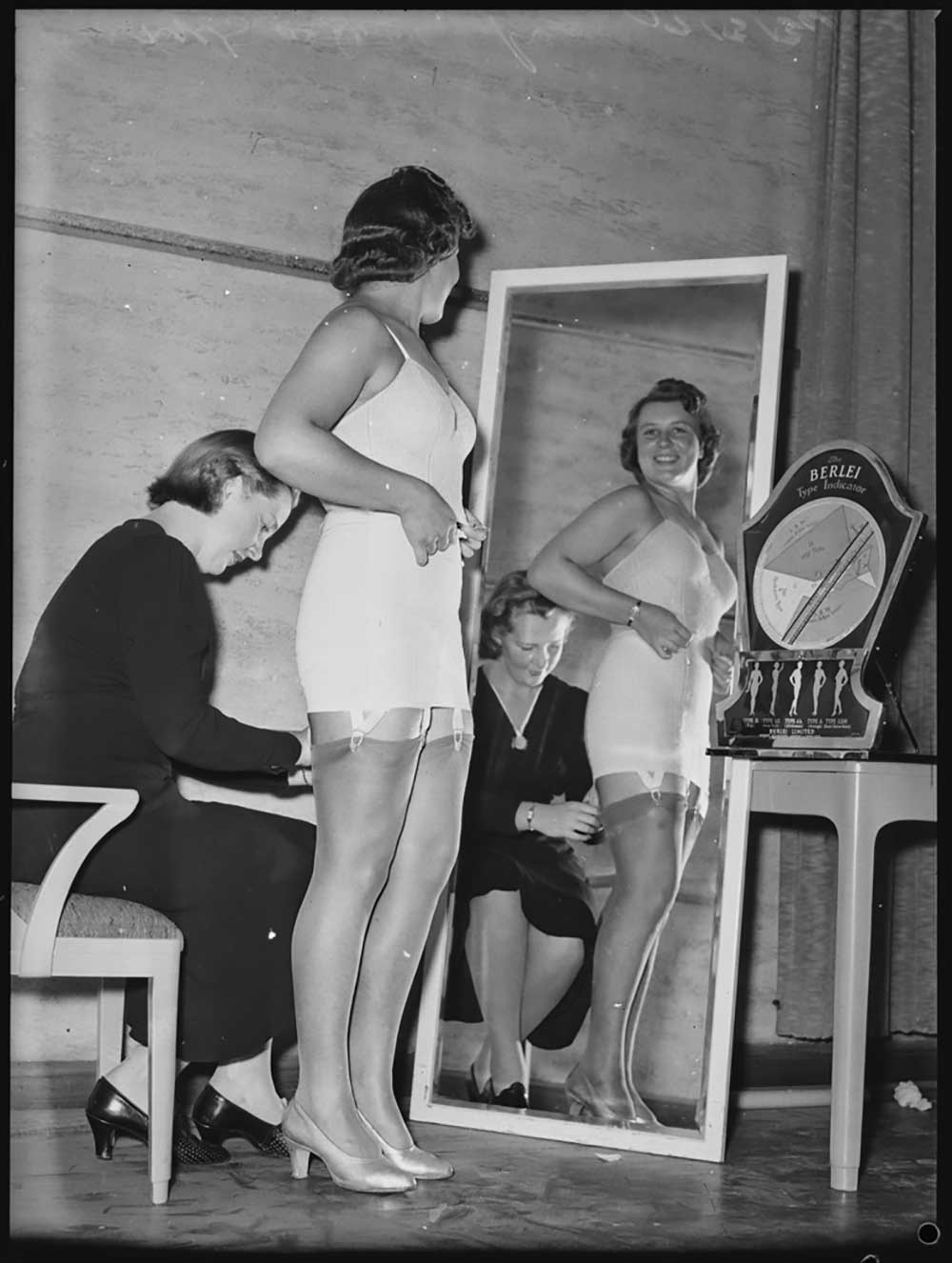

Spurred on by the suffragette movement and emboldened in their new male-dominated roles, women began loudly demanding more practical undergarments. They were fed up with being strapped into cage-like, never-laundered corsets with multiple, bone or steel rod panel supports at the back, front and sides.

Get The Latest News!

Don’t miss our top stories delivered FREE each Friday.

Western women wore the corset in much the same format for 500 years. Over its life, the simple addition of lacing at the back dialled up the torture. ‘Tightlacing’ to achieve the desired 17-to-19-inch (45-to-51cm) waist caused displaced internal organs; broken ribs; collapsed lungs; bruised organs; breathlessness; dizziness and fainting; spinal problems; chronic gastrointestinal issues. It also stunted growth in children who – strapped into the corset as young as three years old – became permanently damaged.

However, it was still advertised as providing support and good posture and made women appear “more attractive, refined, and intelligent.”

Enter Mrs Taylor with her washable, boneless corset, probably best described in The White Ribbon article of March 1916:

“The Camisole Stayette is a garment which is so constructed as to perfect a good figure and improve a bad one.”

Myra Taylor-Farrell invented Australia’s first boneless corset, changing the way women dressed forever.

Myra Taylor offered Australian lingerie giant Berlei the patent and a manufacturing licence. They provided an insulting deal, which she roundly rejected.

Once again, she had been duped by deceitful tactics and betrayal of good faith. Berlei had set about designing their own. However, Mrs Farrell ensured manufacturing, marketing, and sales began in earnest in England. These items were soon on sale in Australia, in direct competition with the yet-to-launch Berlei copy.

Patently talented.

Miss Myra Welsh’s first invention was patented in 1905. Her ingenious mechanical tracing machine could copy single-size sewing patterns from books directly onto the fabric, altering the size. Seamstresses and tailors could now offer made-to-measure garments more efficiently, faithful to the original design.

Myra demonstrating her revolutionary Baby Sling with a local mum, featured in Pix Magazine in 1950.

Mrs Farrell invented the baby sling, allowing mothers to ‘wear’ their babies, freeing them to go about their day. The knapsack, worn at the front of the body, prompted American commentary, which suggested the inventor had stolen the pouch idea from lady kangaroos.

In 1931, her Surfix facelift lifted the skin by “mechanical means” and promised to do away with the aged look.

“Her theory is that wrinkles and sagging occur as the result of tired muscles,” the editorial ran. “The face gets more work and is more exposed than almost any other body part.”

The Surfix muscle lifter.

Mrs Farrell said the muscles were lifted to rest them, allowing the “cell tissues to be built up again.” The device was worn for several months “for mild sagging”. The Surfix was a rubber band attached to plaster pads at the temple, each shaped to support a specific problem muscle.

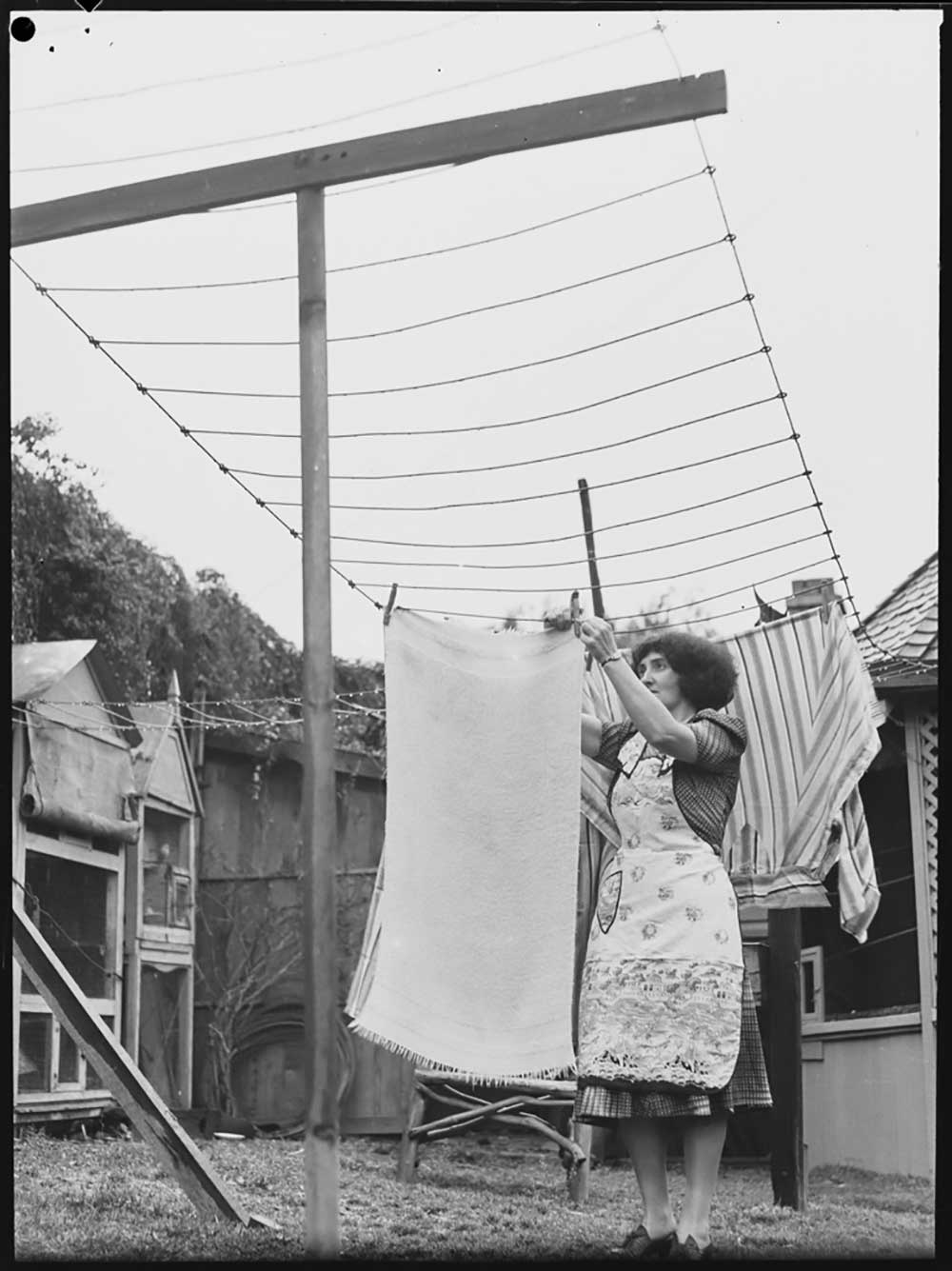

Mrs Farrell’s collapsible, foldable washing line could hold 280 ft (85m) of laundry on its 6-ft by 12 ft (3.6m by 1.8m) area. The drying rack saw the end of people without backyards drying washing on rocks.

She then turned her attention to the more-or-less permanent pole-to-pole backyard clothesline, which wasn’t known for its stability given its ineffective load-bearing attributes. The time-worn design consisted of two poles anchored on either end, each with a floating crossbar strung with rope east to west and susceptible to collapse. The Farrell clothesline kept the two poles and crossbars, but stability was now assured under the design’s better weight-bearing properties. She ran her ropes north to south on shorter lengths, allowing laundry to be hung evenly, and the ropes remained taut.

Myra’s washing line was a game-changer for housewives, able to hold two baskets of wet clothes.

Myra’s Ointment for flour disease (caused by fungus-infested flour) was developed after a commercial baker and neighbour – admitting that the strange lady was her last resort – sought the inventor’s help. By this time, she was covered in festering wounds and severely depressed.

A test patch of the magic cream on her wrist began destroying the fungus within hours. As Mrs Farrell prescribed, the woman took regular hot baths, patted herself dry, and then applied the Ointment liberally before wrapping herself in a sheet to sleep. This she did religiously and was soon cured.

Mrs Farrell invented the linoleum clip, a much simpler way of laying flooring, and gave people the option of sidestepping the cobbler with her attachable sole. “[It] will fit any boot or shoe and requires no tacking on,” she said. The “automatic window” opened and closed at the press of a button was one of hers.

Myra Taylor-Farrell photographed with grand daughter Jennifer in 1939.

She had success with her wheat sampler and weigher and her machine for picking and packing fruit, which ensured fruit arrived at its destination unbruised and untouched by human hands. It was tested on “the most vulnerable fruit”, the mulberry.

Her collapsible, rigid, folding hood could fit any vehicle, which she fitted to a “perambulator” for presentation. These have been continuously in use since. The hood provided stellar protection from the elements and “free ventilation, an automatic air purifier and cooler, which can be adjusted to any requirements [with] its principle a form of condensation”.

Only 11 of her eventual 32 patent applications were well-received and registered in Australia. Mrs Taylor bemoaned the obstacles she faced in moving things along:

“It is so difficult to get anything done in Australia, and we are so slow and cautious about assimilating new ideas,” she told The White Ribbon.

In a rare description of Myra Taylor, the newspaper had this to say:

“One would expect to find the person responsible for all this ingenious work to be rather difficult, but Mrs Taylor is quite the reverse when one succeeds in making her talk of herself and her doings. Her manner is simple, kindly, and affable. She is feminine, fair, and plump, with appealing blue eyes and a brilliant colouring, which comes and goes as she warms to her subject, and a soft, slow voice.”

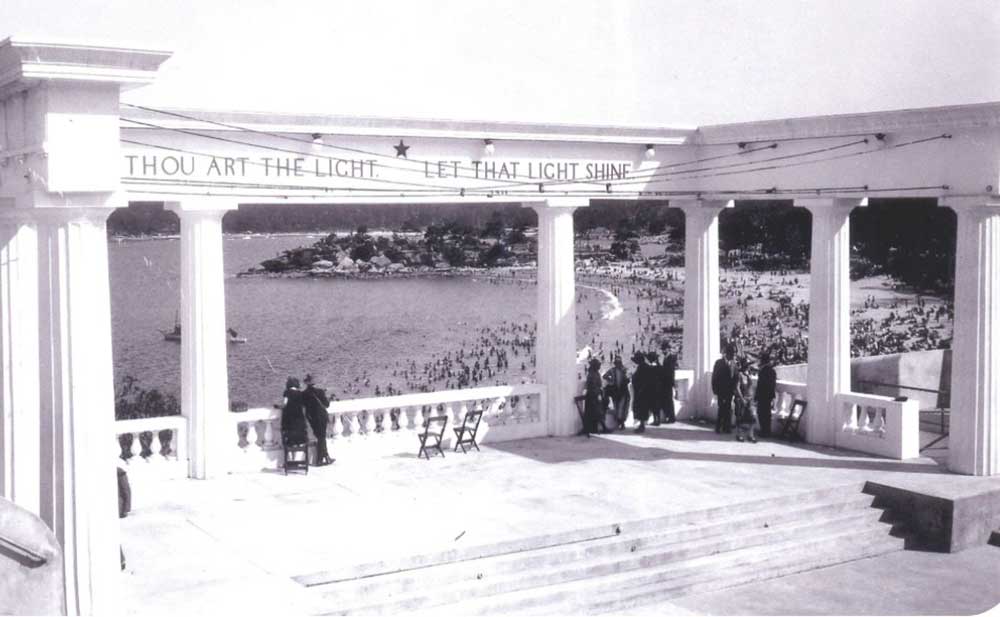

The Star Amphitheatre in Balmoral was built for the Messiah’s second coming in 1922.

While Mrs Farrell still tinkered away in her backyard shed during her early life in Mosman, it became apparent that by 1922 she had sought a broader church. She became well known in theosophical circles and gravitated towards the Order of the Star in the East’s “system of living”, which had revived aspects of the occult.

She took out a subscription to help fund The Star Amphitheatre at Balmoral, completed in 1922. The grand structure would cost 16,000 pounds (now about one million dollars).

Devotees built this to welcome to Australia the apolitical, psychic, humanist, guru, and leader of the Star of the East movement, 17-year-old Indian national Jiddu Krishnamurti. He was eagerly greeted by those who’d forked out small fortunes to have their name etched into one of the arena’s stone benches, allegedly for posterity. The theater, which sat at the northern end of Balmoral above Edwards Beach, was demolished in 1951 to make way for a block of flats.

An accomplished artist in later life, many of Myra’s works have disappeared.

Studying under a stage-scenery painter, Mrs Farrell also became an accomplished painter after the style of the Impressionists. Though many of her smaller paintings have survived, larger pieces did not – besides the most well-known of her larger artworks, Seascapes, painted around 1938.

The Egyptian angle.

Mrs Farrell kept an Egyptian mummy’s foot on her Mosman mantelpiece, the provenance of which is unknown. However, by the close of WWI, illegal archaeological digs had sprung up in Egypt, egged on by a healthy, global black-market for mummified body parts and sundry trinkets.

After her death, the gruesome item was dumped in the rubbish, where it was discovered by the garbage man, who took it to the police, though records of any formal investigation could be located.

Myra Taylor-Farrell died in Mosman in 1957, aged 79.

Only scant details of her patents and designs are accessible. Of course, gaining a patent required secrecy and careful vigilance lest one’s designs be copied ahead of a tick from the Patent Office – a lesson she had well learned. This may account for the elusive detail.

Death of a quiet achiever.

Myra Juliet Farrell died at her Prince Albert Street, Mosman home on 8 March 1957, aged 79. The house was last sold on 8 March 2018 – the 61st anniversary of her death. The date is also reserved for International Women’s Day. A search of Australia’s notable people who have been immortalised via a plaque, statue, street name, or another monument – or made it to official International Women’s Day lists – revealed no acknowledgement of Myra Farrell.

GOT A NEWS TIP? GET IN TOUCH!

Email: [email protected]

Get The Latest News!

Don’t miss our top stories delivered FREE each Friday.